Page path:

- Press Office

- Bacterial Individualism: A Survival ...

Bacterial Individualism: A Survival Strategy for Hard Times

May 11, 2016

Whether you are a human or a bacterium, your environment determines how you can develop. In particular, there are two fundamental problems. First: what resources can you draw on to survive and grow? And second: how do you respond if your environment suddenly changes?

A group of researchers from Eawag, ETH Zurich, EPFL Lausanne, and the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen recently discovered that the number of individualists in a bacterial population goes up when its food source is restricted. Their finding goes against the prevailing wisdom that bacterial populations merely respond, in hindsight, to the environmental conditions they experience. Individualists, the study finds, are able to prepare themselves for such changes well in advance.

A group of researchers from Eawag, ETH Zurich, EPFL Lausanne, and the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen recently discovered that the number of individualists in a bacterial population goes up when its food source is restricted. Their finding goes against the prevailing wisdom that bacterial populations merely respond, in hindsight, to the environmental conditions they experience. Individualists, the study finds, are able to prepare themselves for such changes well in advance.

Scarcity fosters diversity, diversity promotes flexibility

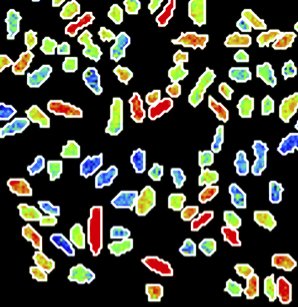

In a recent paper in the journal Nature Microbiology, researchers working with Frank Schreiber have shown that individual cells in bacterial populations can differ widely in how they respond to a lack of nutrients. Although all of the cells in a group are genetically identical, the way they process nutrients from their surroundings can vary from one cell to another. For example, bacteria called Klebsiella oxytoca preferentially take up nitrogen from ammonium (NH4+), as this requires relatively little energy. When there isn’t enough ammonium for the entire population, some of the bacteria start to take up nitrogen by fixing it from elementary nitrogen (N2), even though this requires more energy. If the ammonium suddenly runs out altogether, these cells at least are prepared. While some cells suffer, the group as a whole can continue to grow. “Although all of the bacteria in the group are genetically identical and exposed to the same environmental conditions, the individual cells differ among themselves,” says Schreiber.

Detailed insights thanks to the latest technology

Schreiber and his colleagues were only able to reveal the astonishing differences between the bacteria by studying them very closely. “We had to measure nutrient uptake by individual bacterial cells – even though these are only 2 μm large,” explains Schreiber. “Usually, microbiologists study the collective properties of millions or even billions of bacteria. It was only thanks to the close collaboration between the research groups, and by pooling our expertise and technical equipment, that we were able to study the bacteria in such detail.”

Detailed insights thanks to the latest technology

Schreiber and his colleagues were only able to reveal the astonishing differences between the bacteria by studying them very closely. “We had to measure nutrient uptake by individual bacterial cells – even though these are only 2 μm large,” explains Schreiber. “Usually, microbiologists study the collective properties of millions or even billions of bacteria. It was only thanks to the close collaboration between the research groups, and by pooling our expertise and technical equipment, that we were able to study the bacteria in such detail.”

Bacteria are individualists, too

The present study shows to what extent individuality – in bacteria and in general – can be essential in a changing environment. Differences between individuals give the group new properties, enabling it to deal with tough environmental conditions. “This indicates that biological diversity does not only matter in terms of the diversity of plant and animal species but also at the level of individuals within a species,” says Schreiber.

Next, Schreiber and his colleagues plan to study whether the individualistic behavior of specific individuals is of equal importance in natural environments.

The present study shows to what extent individuality – in bacteria and in general – can be essential in a changing environment. Differences between individuals give the group new properties, enabling it to deal with tough environmental conditions. “This indicates that biological diversity does not only matter in terms of the diversity of plant and animal species but also at the level of individuals within a species,” says Schreiber.

Next, Schreiber and his colleagues plan to study whether the individualistic behavior of specific individuals is of equal importance in natural environments.

Original publication

Phenotypic heterogeneity driven by nutrient limitation promotes

growth in fluctuating environments

Frank Schreiber, Sten Littmann, Gaute Lavik, Stéphane Escrig, Anders Meibom, Marcel Kuypers, Martin Ackermann. Nature Microbiology. DOI : http://doi.org10.1038/NMICROBIOL.2016.55

Frank Schreiber, Sten Littmann, Gaute Lavik, Stéphane Escrig, Anders Meibom, Marcel Kuypers, Martin Ackermann. Nature Microbiology. DOI : http://doi.org10.1038/NMICROBIOL.2016.55

For further inquiries

Frank Schreiber / +49 30 8104-1414/ [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Marcel Kuypers / +49 421 2028 602 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Martin Ackermann / +41 58 765 5122 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

or the press service

Dr. Manfred Schlösser / +49 421 2028 704 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger / +49 421 2028 947 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Andri Bryner / +41 58 765 51 04 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Marcel Kuypers / +49 421 2028 602 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Martin Ackermann / +41 58 765 5122 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

or the press service

Dr. Manfred Schlösser / +49 421 2028 704 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger / +49 421 2028 947 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Andri Bryner / +41 58 765 51 04 / [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Participating institutes

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland

ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Eawag, Dübendorf and Kastanienbaum, Switzerland

École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland

ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Eawag, Dübendorf and Kastanienbaum, Switzerland