- Press Office

- Influence of carbon dioxide leakage on the seabed

Influence of carbon dioxide leakage on the seabed

Day-in, day-out, we release nearly 100 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. One possible measure against steadily increasing greenhouse gases is known as CCS (carbon capture and storage): Here, the carbon dioxide is captured, preferably directly at the power plant, and subsequently stored deep in the ground or beneath the seabed. However, this method poses the risk of reservoirs leaking and allowing carbon dioxide to escape from the ground into the environment. The European research project ECO2, coordinated at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, addresses the question of how marine ecosystems react to such CO2-leaks. The field study of an international group of researchers headed by Massimiliano Molari from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen and Katja Guilini from the University of Ghent in Belgium, now published in Science Advances, reveals how leaking CO2 affects the seabed habitat and its inhabitants.

Substantial changes to algae, animals and microorganisms

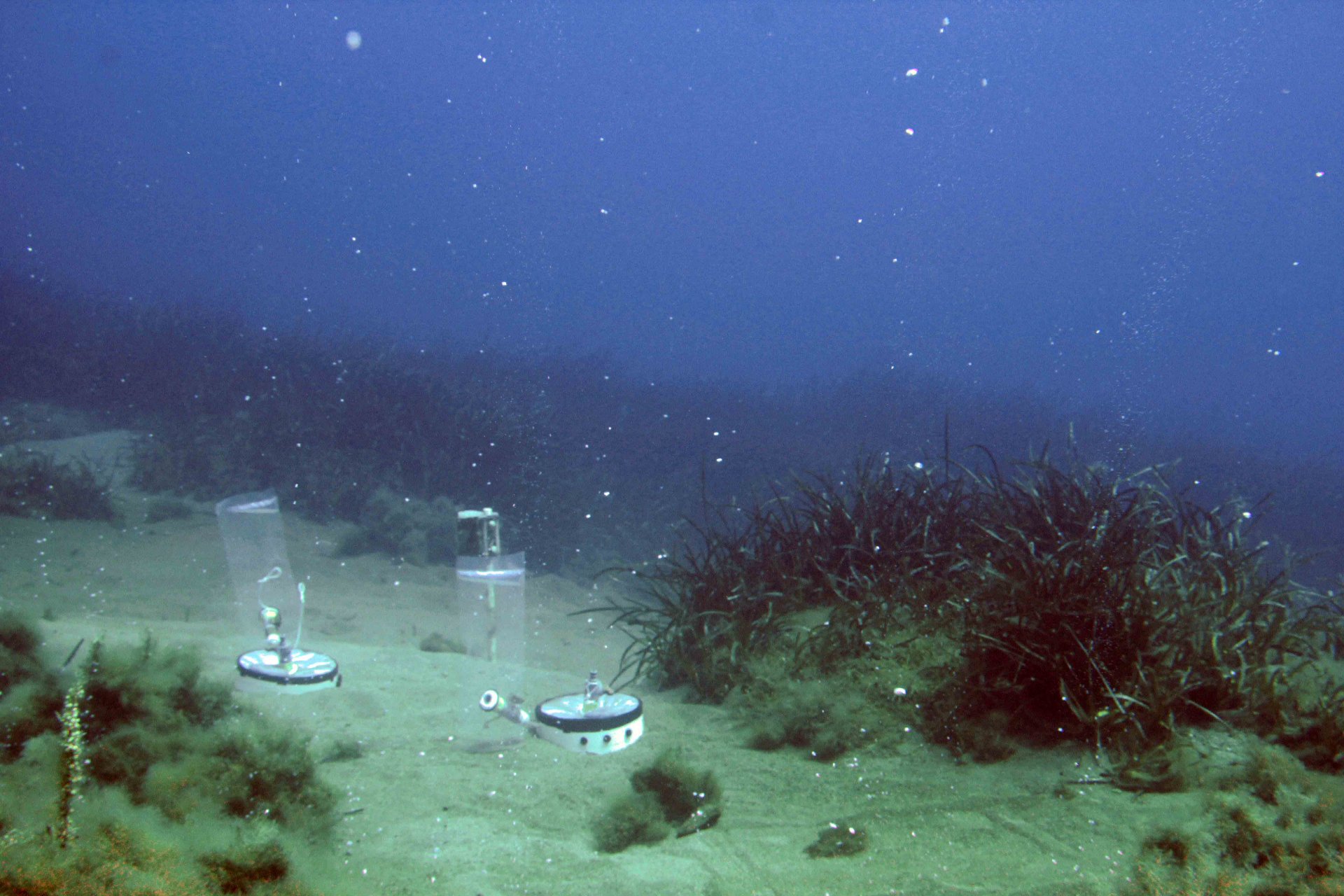

For their study, the researchers visited natural leaks of CO2 in the sandy seabed off the coast of Sicily. They compared the local ecosystem with locations without CO2-venting. In addition, they exchanged sand between sites with and without CO2-venting in order to study how the bottom-dwellers respond and if they can adapt. Their conclusion: Increased CO2 levels drastically alter the ecosystem. “Most of the animals inhabiting the site disappeared due to the effect of the leaking CO2”, Massimiliano Molari reports. “The functioning of the ecosystem was also disrupted – and what’s more, long-term. Even a year after the CO2-vented sediment had been transported to undisturbed sites, its typical sandy sediment community had not established.”

The researchers report the following details:

- Together with the ascending gas bubbles, nutrients were transported to the surface. As a result, tiny algae in the sand grew much better.

- The small and larger animals (invertebrate meio- to marofauna) inhabiting the sand were affected particularly badly by a CO2 leak: their numbers and diversity fell considerably with increasing carbon dioxide levels. The biomass of the animals dropped to a fifth, although more food was actually available due to the numerous small algae

- The numbers of seabed-dwelling microorganisms did not drop as CO2 increased, but their composition changed substantially.

- The modified community of organisms led to a change in the entire ecosystem. Most inhabitants cannot adapt to the altered environmental conditions in the long term. Instead, few species, which can cope better with the increased CO2 levels, populate the sand.

“A leak in a carbon storage system beneath the sea fundamentally alters the chemistry of sandy seabeds and subsequently the function of the entire ecosystem”, Molari summarizes. “That is, there is a considerable risk that a carbon dioxide leak will harm the local ecosystem. These carbon dioxide storage systems can nevertheless globally reduce the impact of climate change.”

A first holistic overview

For the first time, this current study delivers a “holistic” view of the effects of increasing CO2 concentrations on the seafloor. It considers both biological and biogeochemical processes and different levels of the food chain, from microbes to large invertebrate animals.

CCS facilities are already in operation, for example off the Norwegian coast. Within the European Union, CCS is considered a key technology for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. “Our results clearly reveal that the site selection and planning of carbon storage systems beneath the seabed also demand a detailed study of the inhabitants and their ecosystem in order to minimize harm”, emphasizes principal investigator Antje Boetius. „Having said that, global marine protection also includes taking measures against the still high CO2-emissions.“

Further Information:

Further Links:

ECO2 - Project: www.eco2-project.eu/home.html

Original publication:

Massimiliano Molari, Katja Guilini, Christian Lott, Miriam Weber, Dirk de Beer, Stefanie Meyer, Alban Ramette, Gunter Wegener, Frank Wenzhöfer, Daniel Martin, Tamara Cibic, Cinzia De Vittor, Ann Vanreusel, Antje Boetius (2018): CO2 leakage alters biogeochemical and ecological functions of submarine sands. Sci. Adv. 2018. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aao2040

Participating institutes:

- HGF-MPG Joint Research Group on Deep Sea Ecology and Technology & Microsensor Group, Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, 28359 Bremen, Germany

- Marine Biology Research Group, Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- HYDRA Institute for Marine Sciences, Elba Field Station, Via del Forno 80, 57034 Campo nell’Elba (LI), Italy

- MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University Bremen, 28359 Bremen, Germany

- HGF-MPG Joint Research Group on Deep Sea Ecology and Technology, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

- Centre d’Estudis Avançats de Blanes (CEAB), Consejo Superior de Investiga- ciones Cientificas (CSIC), Blanes, Girona, Catalunya, Spain

- Sezione di Oceanografia, Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e di Geofisica Sperimentale – OGS, I-34151 Trieste, Italy

Please direct your queries to:

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |