- Press Office

- Press releases 2019

- The Microbe of the Year 2019: The world's smallest compass needle

The Microbe of the Year 2019: The world's smallest compass needle

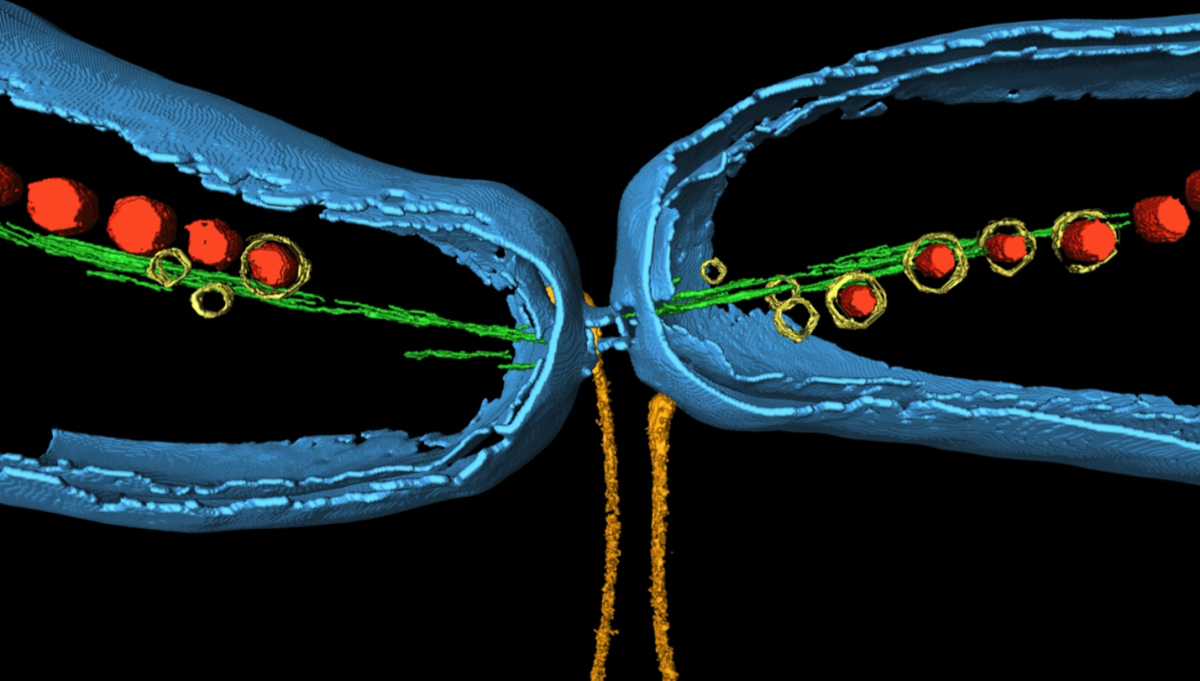

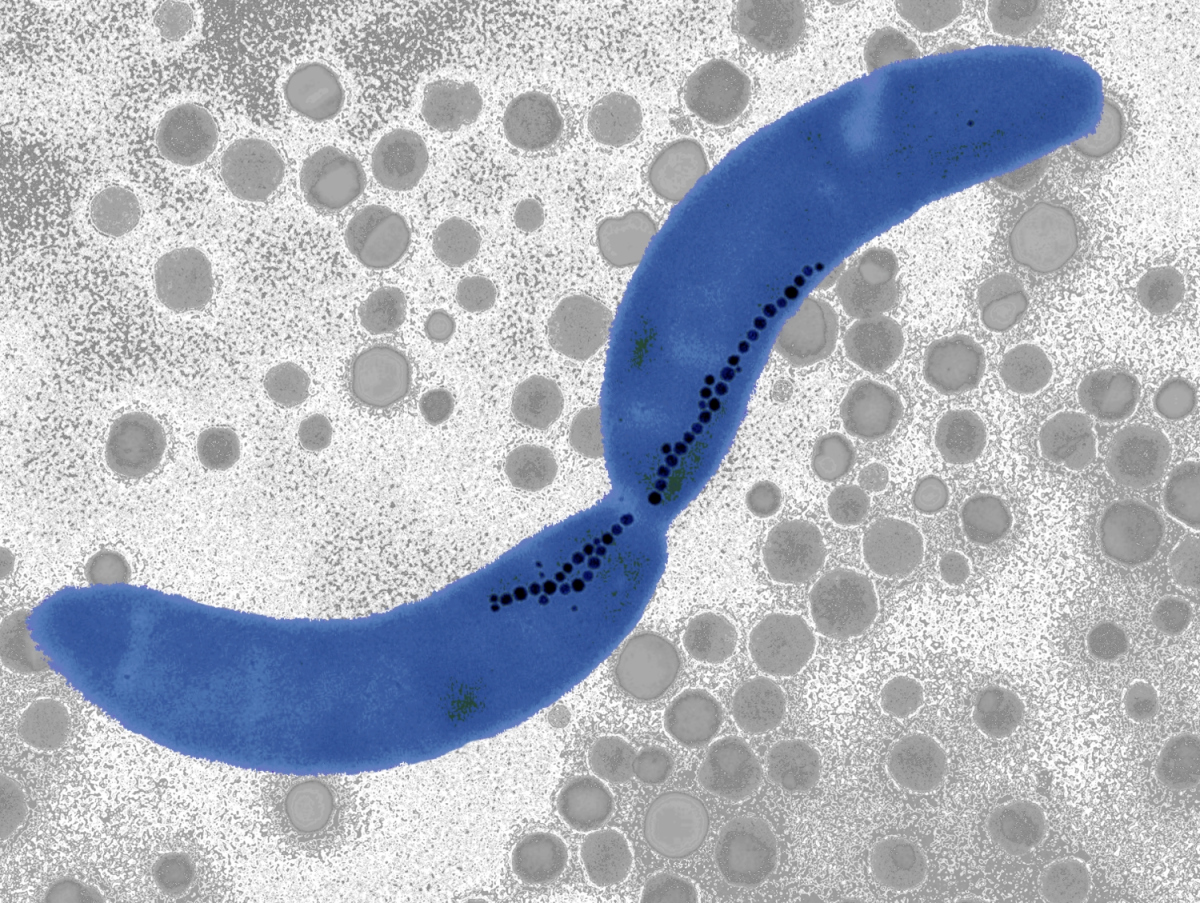

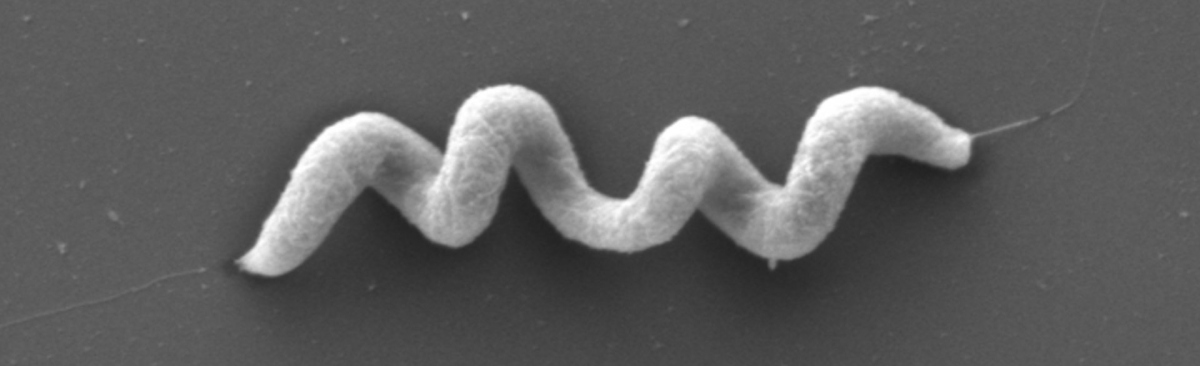

The Magnetic Spiral from Greifswald is officially called Magnetospirillum gryphiswaldense. The genus Magnetospirillumhas a very special ability: It contains a tiny magnetic needle. This needle, composed of nanoscopic crystals of a magnetic iron oxide, allows this microbe to orient itself to the Earth's magnetic field. The microbe uses this ability, together with a built-in oxygen sensor, to navigate into just the right layer of mud in which it feels most comfortable.

Magnetospirillum at the Max Planck Institute in Bremen

In the early sixties, Salvatore Bellini from Italy discovered the first so-called magnetotactic bacteria. However, their exploration didn’t quite get under way. In 1990, Dirk Schüler, then a student in Greifswald, succeeded in isolating Magnetospirillum from the mud of a small river. This made research much easier: Now these bacteria could be efficiently cultivated and soon after also genetically manipulated.

A few years later, Schüler moved to Bremen to work at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, where he headed a junior research group from 1999 to 2006. Again, he devoted himself to revealing the secrets of magnetic bacteria. Together with the institute’s Director Rudolf Amann, the now emeritus director Friedrich Widdel and other scientists, he investigated their biodiversity in sediments of lakes and coastal seas. "Another research focus of Schüler’s research group at the Max Planck Institute in Bremen was the formation and arrangement of the magnetic particles, the so-called magnetosomes, inside the Magnetospirillum cells," says Amann.

For Schüler, who holds the chair of microbiology at the University of Bayreuth since 2014, the time in Bremen was very important. "Thanks to the freedom of research at the Max Planck Institute and the many opportunities for cooperation, I was able to lay important foundations for my further research on magnetic bacteria," he explains.

From fossils to microrobots

In geophysical terms, magnetic bacteria are also an exciting research object: Once the bacteria die, the magnetosomes are released. They often remain in the soil and, as fossils, reveal important details about how the Earth's magnetic field has changed in earlier times.

But Magnetospirillum is not only interesting for a better understanding of nature. Biotechnological applications are also becoming increasingly important. The tiny magnets are very similar in size and shape and are highly magnetized. To date, it has not been possible to artificially produce particles with such precision and properties. They could be used as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other biomedical applications. Magnetosomes might help fighting tumours. Also, magnetic microbes could be loaded with drugs and then directed right to a desired site of action in the body - microrobots as tiny ambulances. Schüler's current research, funded by the renowned ERC Advanced Grant, also focuses on biotechnological aspects, amongst others. He and his colleagues hope to develop and test new methods to transfer magnetic properties to organisms that do not naturally have such properties.

Microbiology in the garden pond

Now - would you like to take a look at the magnetic microbes yourself? It's not that difficult: For example in a pond or stream, there are many different types: rods, spheres, spirals and even multicellular consortia. “With a microscope magnifying at least 100 times, you look at the edge of a drop of mud to which you hold a small rod magnet,” explains Schüler. “The magnetic bacteria persistently swim in one direction and collect at the edge of the drop, on the magnetic south pole.” If you turn over the magnet, the bacteria also turn. “If you’ve ever enriched bacteria with a simple magnet and examined them under the microscope, you will not forget the eureka effect.”

Fanni Aspetsberger

For further information:

Please direct your queries to:

Department of Microbiology

University of Bayreuth

Prof. Dr. Dirk Schüler

phone: +49 (0)921 55-2729

dirk.schueler![]() uni-bayreuth.de

uni-bayreuth.de

Director

Max Planck Institut for Marine Microbiology Bremen

Prof. Dr. Rudolf Amann

phone: +49 (0)421 2028-930

[Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]