- Abteilungen

- Abteilung Symbiose

- Forschungsgebiet

- Symbioses from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps

Symbioses from hydrothermal vents and cold seeps

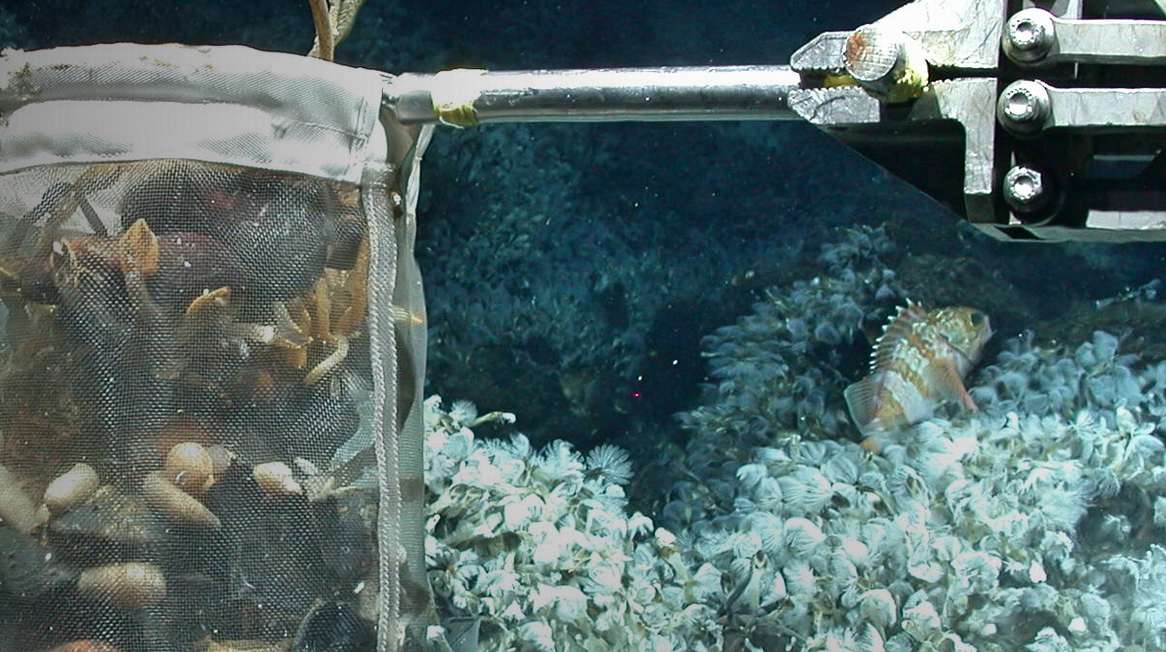

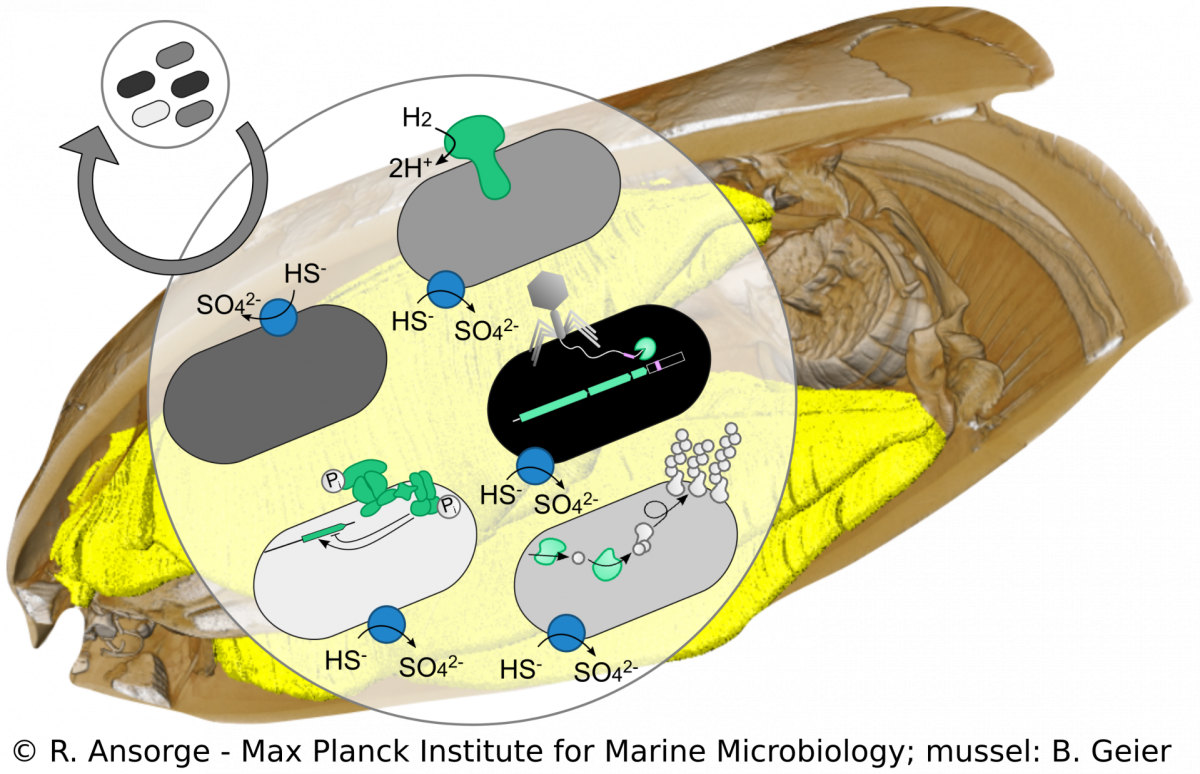

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents and cold seeps are colonized by dense communities of animals hosting chemosynthetic symbiotic bacteria that provide them with nutrition. These symbionts use geofuels such as methane, reduced sulfur compounds and hydrogen, emitted from the sea floor at vents and seeps, as an energy source to fix inorganic carbon or methane into biomass. The establishment of symbioses with chemosynthetic bacteria as primary producers is the evolutionary innovation that allowed invertebrate animals to thrive in these extreme habitats where the input of organic matter from photosynthesis is extremely low.

Symbioses in Bathymodiolus mussels

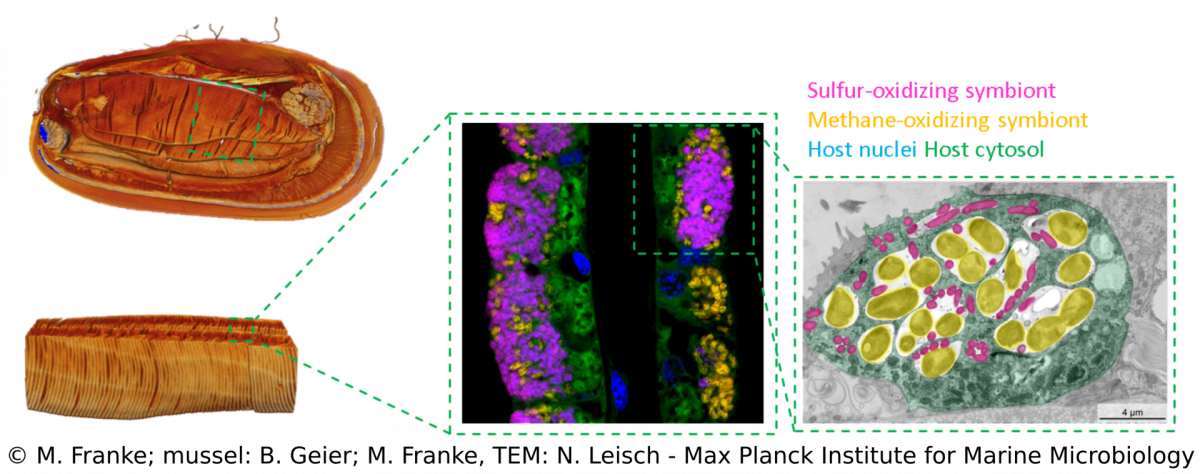

Bathymodiolus mussels are widespread throughout the world’s oceans. They occur at hydrothermal vents and cold seeps where they are one of the most dominant animals and grow to large abundances and biomass. Their success in these habitats is facilitated by beneficial symbiotic bacteria that are hosted within specialized gill cells called bacteriocytes. These symbionts can turn chemical energy from hydrothermal fluids into biomass to feed their mussel hosts. Through such chemosynthetic processes, the mussels are independent of surface-derived food sources. Bathymodiolus mussels live a in symbiosis with sulfur-oxidizing symbionts, that can use reduced sulfur compounds or hydrogen as energy source, and/or methane-oxidizing symbionts that thrive on methane.Our research aims to understand the evolutionary history, development and host-symbiont interaction of these symbioses.

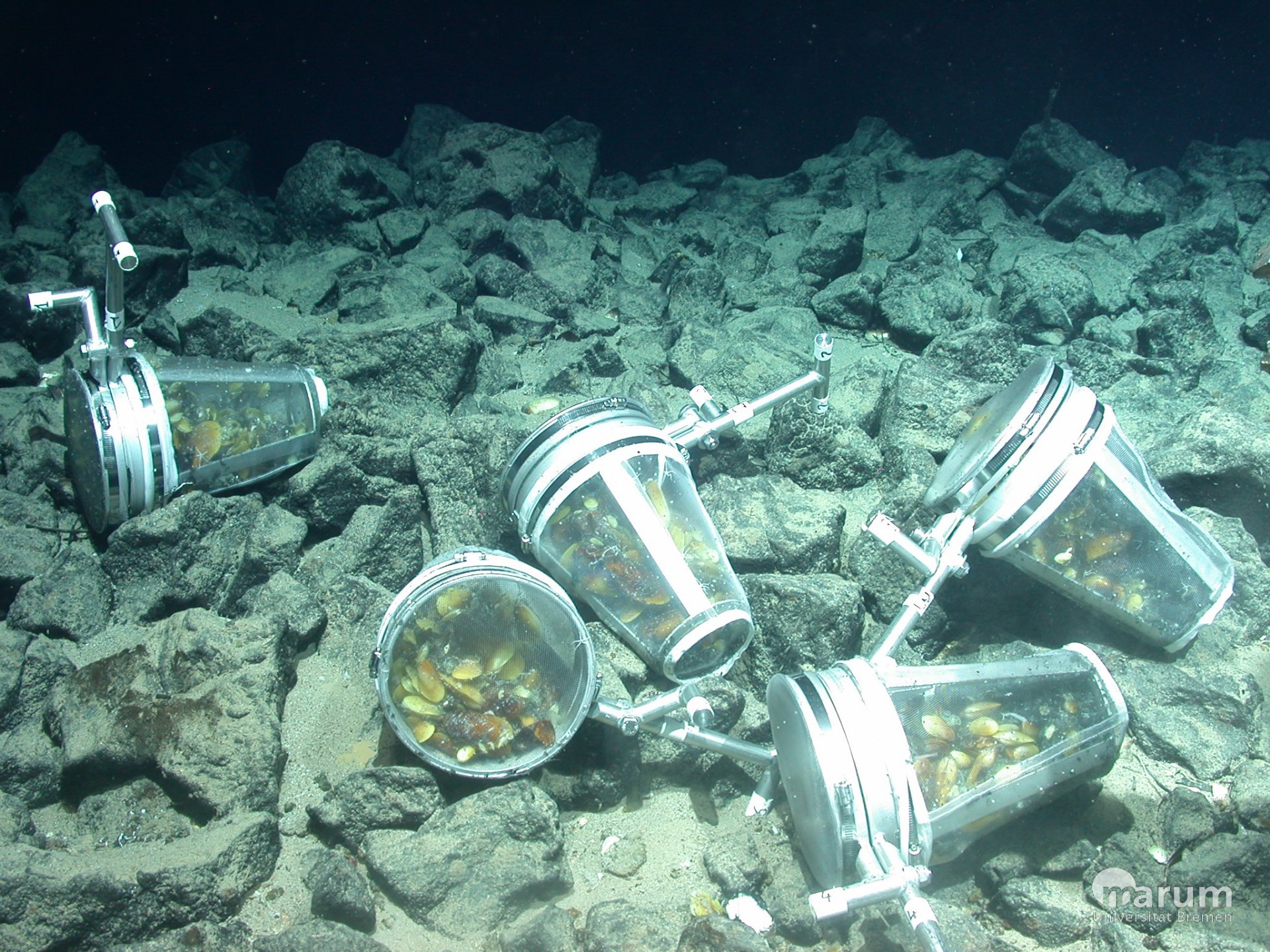

We combine a variety of techniques (e.g. metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, lipidomics) that allow us to investigate Bathymodiolus symbioses from a global geographic distribution down to a fine-scale resolution that can visualize spatial patterns within single hosts (e.g. FISH, TEM, MALDI). Over the years, we discovered more complex Bathymodiolus symbioses with a higher symbiont diversity. For example, we recently found a high diversity at strain-level in the sulfur-oxidizing symbionts. Apart from the well-studied beneficial symbionts, Bathymodiolus mussels associate with a range of bacteria whose role in the symbiosis is less clear, such as Ca. Endonucleobacter, which infects the nuclei of mussels cells. We also recently identified spirochaetes in mussels from the Kermadec Arc with completely unknown functions.The symbionts of Bathymodiolus mussels are thought to be horizontally transmitted, which means they are taken up from the environment with each new host generation. This mode of acquisition opens up many new questions that we are investigating – such as How do host and symbionts recognize each other? How long is the time window for symbiont acquisition? Is there an active free-living stage of the symbionts? What makes them different from their free-living relatives?

Overview of projects & people

Population genetics of bathymodiolin mussels of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge - Karina van der Heijden

Population genomics of mussels at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge & mussel symbioses worldwide - Christian Borowski

Population genomics of the Bathymodiolus symbiosis, symbionts in Bathymodiolus hybrids & free-living stage of symbionts - Merle Ücker

Development of Bathymodiolus mussels, symbiont colonization and trophic relation between larvae and adults - Maximilian Franke

Bathymodiolus ultrastructure - Niko Leisch

Spatial metabolomics and correlative 3D histology - Benedikt Geier

Lipidomics in Bathymodiolus mussels - Dolma Michellod

Physiological response of Bathymodiolus hosts and symbionts to stress as revealed by transcriptomics (and proteomics) - Målin Tietjen

Microscopy, phylogeny and molecular biology of Endonucleobacter & SOX strain mosaicism in Bathymodiolus azoricus - Miguel Ángel González-Porras

Strain diversity and evolution in endosymbionts of Bathymodiolus mussels & genome structure in the bacterial SUP05 clade - Rebecca Ansorge

Metabolic investigation of cultivable symbiont relatives - Patric Bourceau

Population genetics of Bathymodiolus at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

K. van der Heijden, C. Borowski

The aim of this study is to shed light on the evolutionary history of Bathymodiolus mussels at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Previous phylogenetic analyses of the mussels showed that the classical marker gene for phylogenetic assessment, the mitochondrial mtCOI, does not provide enough resolution to clarify the relationship within this group.

To investigate the geographic structure, gene genealogies, and the major directions and relative amounts of historical gene flow between the four mussel populations at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, we are using a multi-locus approach for this population genetic study. The results of our analyses are used to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the mussel populations which also provides us with insight on the colonization history of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

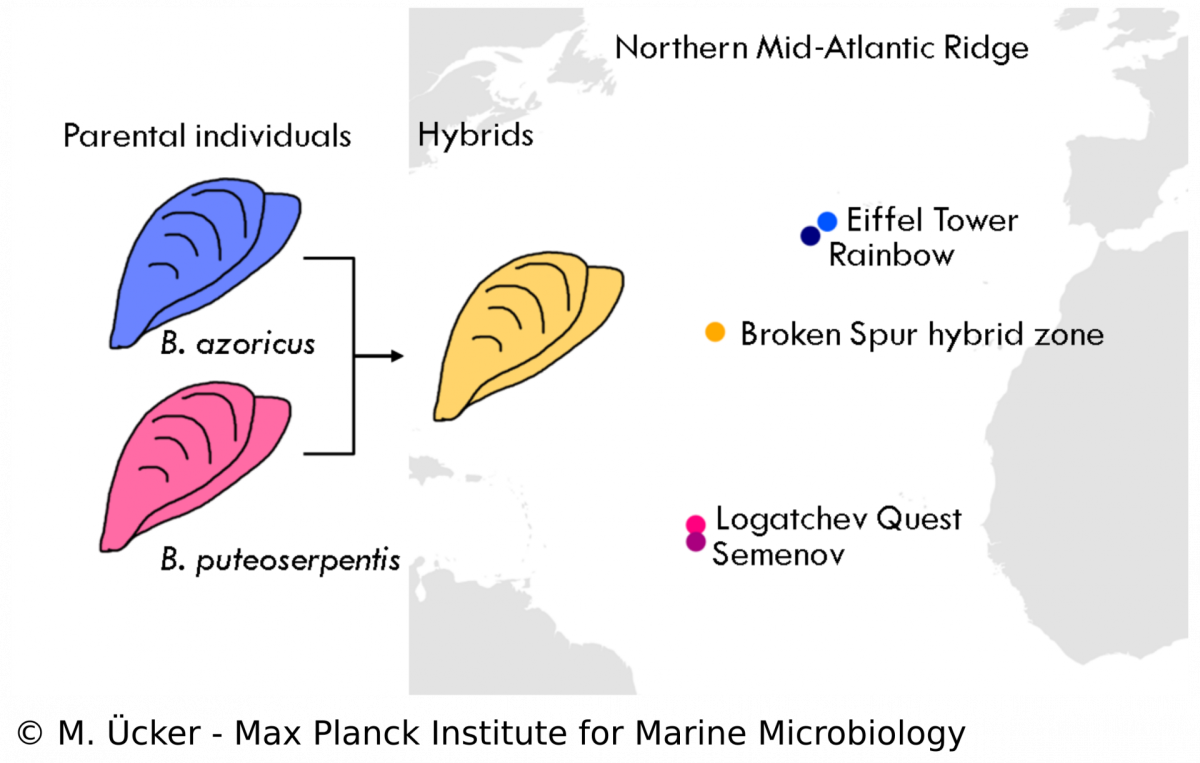

Symbionts in a mussel hybrid zone

In the Bathymodiolus symbiosis, little is known about the influence of the symbionts on the evolution of the host despite many studies that have been performed on the symbionts‘ physiology. Our study aims to understand the population structure and dynamics of Bathymodiolus mussels and the role of symbioses in animal hybridisation. We analyse mussel samples from a vent field at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where two mussel species, B. azoricus and B. puteoserpentis, have been described to form viable hybrids. We use diagnostic markers and metagenomic techniques to assess the hybrid status of each mussel individual and to investigate the phylogeny of host mitochondria and the symbionts. We hope to shed new light on the symbiosis in hybrid Bathymodiolus mussels and investigate questions of symbiont specificity and recognition. Understanding hybridisation in symbiotic animals allows us to study species formation and evolution in natural communities and the role of bacterial symbionts in these processes.

Development of Bathymodiolus mussels & symbiont colonization

M. Franke, N. Leisch

Adult Bathymodiolus mussels harbour their primary symbionts in the gill tissue. In juvenile mussels however, the symbionts colonize not only the gills but also all other epithelial tissues within the mantle cavity. Only little is known about how and when symbionts first colonize the mussels. To understand the processes and preferences of symbiont colonization, we examine early developmental stages of Bathymodiolus mussels. Using a correlative imaging approach, which unites light- and electron microscopy with synchrotron radiation-based X-ray micro tomography, we are able to generate a detailed three-dimensional morphological dataset. This dataset can be combined with symbiont localization using 16S rRNA FISH and allows us to determine the time of symbiont colonization revealed by distinct morphological adaptations during the development of the host. Our work serves as a starting point for further functional analyses to elucidate how bacteria can influence and shape early eukaryotic development.

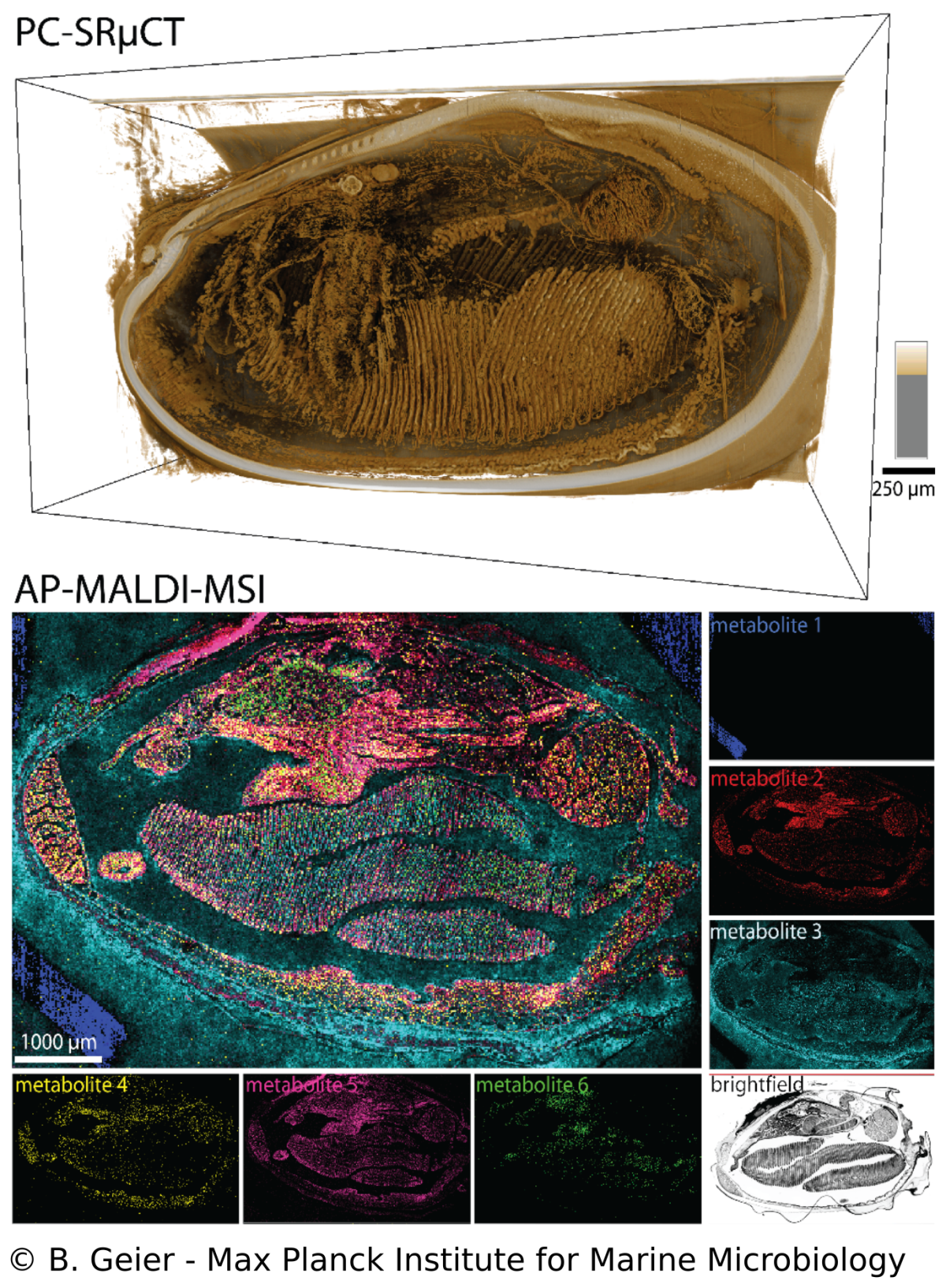

Spatial metabolomics and correlative 3D histology

B. Geier, M. Franke, E. Sogin, D. Michellod, M. Á. Gónzalez-Porras, A. Gruhl, N. Leisch, M. Liebeke

Endosymbioses such as in Bathymodiolus mussels are characterized by intimate metabolic interactions among the symbiotic partners. Yet, we know very little about the nature of these interactions in symbioses, particularly in their environmental context. Therefore, we created a spatial metabolomics pipeline (metaFISH) that links symbiont genotypes with metabolic phenotypes to allow a spatial assignment of host and symbiont metabolites at the scale of individual host cells. We could observe how the spatial chemistry of host cells differs with the presence of intracellular symbionts, found variations in metabolic phenotypes in a single symbiont type and detected novel metabolites. To gain a broader understanding of metabolite distribution at the scale of whole animals, we also developed a correlative workflow that allows imaging the 3D anatomy and molecular composition of animal-microbe systems. The high spatial resolution gained be these imaging approaches allows us to tackle some of the fundamental question in symbiosis research such as how do the symbiotic partners interact.

Physiological reponse of Bathymodiolus symbiosis to environmental change

To understand the cellular interactions between Bathymodiolus mussels and their intracellular symbionts, we make use of advanced next-generation sequencing techniques and investigate gene expression patterns of both partners. In particular, we are investigating which gene (groups) are responsible for the maintenance of the symbiosis in the light of changing environmental conditions. One example for such conditions is the limited access to hydrothermal fluids that carry essential energy sources for the symbionts such as sulfur or methane. Such varying conditions are expected to occur regularly in hydrothermal systems. We simulate such conditions with in situ and laboratory experiments, and compare the physiological responses of both host and symbionts on the transcriptome and proteome level.

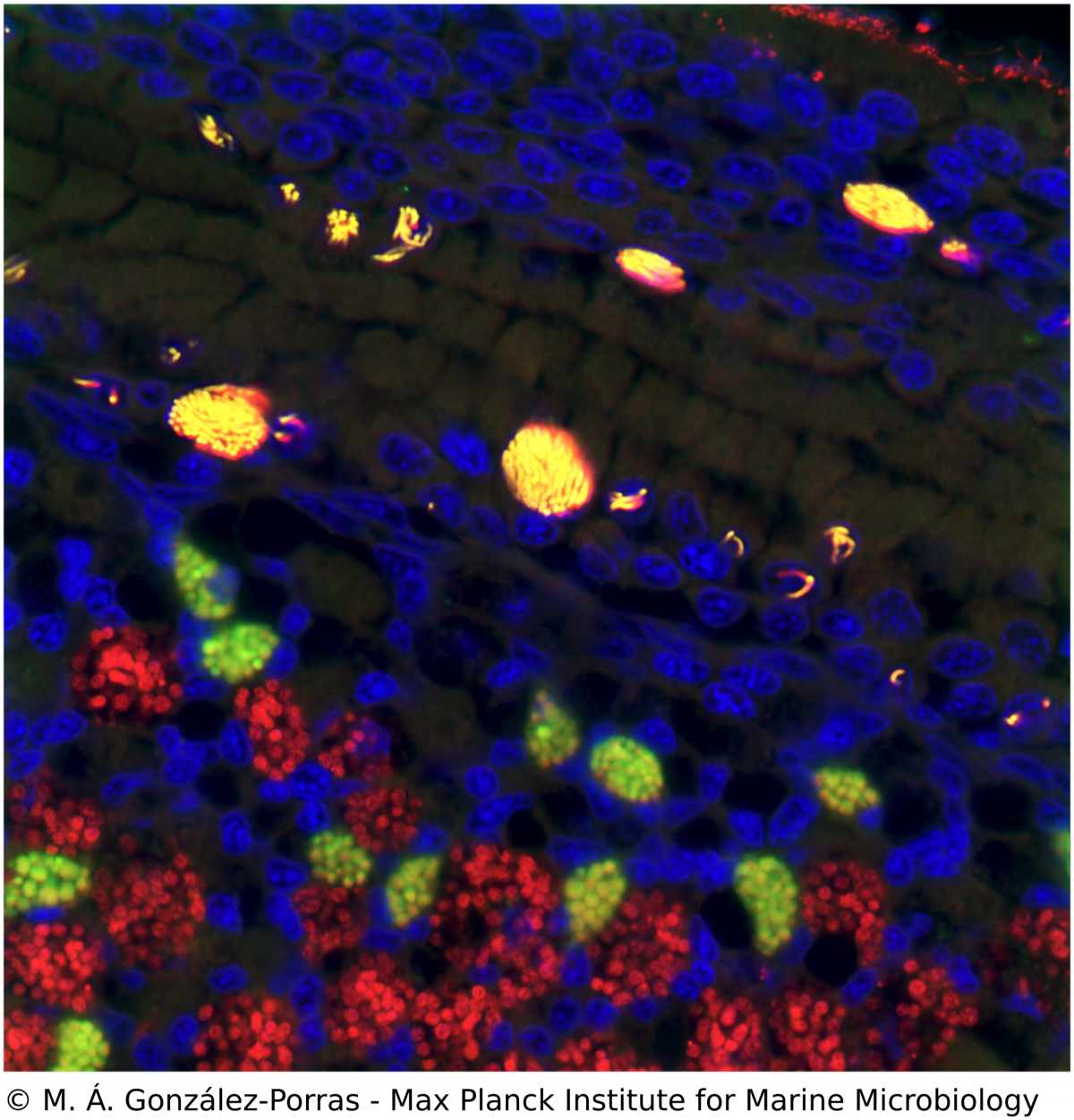

Microscopy, phylogeny and molecular biology of Endonucleobacter

M. Á. Gónzalez-Porras, N. Leisch

Ca. Endonucleobacter is a gammaproteobacterial parasite that infects the nuclei of Bathymodiolus mussels. After a single Ca. Endonucleobacter cell invades the host nucleus, it proliferates massively (up to 80,000 bacteria per nucleus) and the volume of the nucleus increases up to 50 fold. We investigate how Ca. Endonucleobacter thrives in the nucleus, how it affects host cells and how it prevents the shutdown of the eukaryotic cell (e.g. apoptosis). To do so, we have sequenced the genome of the parasite and coupled laser capture microdissection of infected nuclei with ultra-low-input RNA-sequencing. We are now investigating how the transcriptional profiles of parasite and host change along the infectious cycle. By targeting the transcriptomic profiles of specific life stages of an intranuclear parasite in situ, our pipeline closes the gap between the visual, molecular and temporal characterization of a parasite-host interaction.

Strain diversity of Bathymodiolus symbionts

R. Ansorge, M. Á. Gónzalez-Porras

Beyond species boundaries, small genomic changes can strongly impact the lifestyle of a bacterial strain. However, currently it is not well understood how strain-level diversity in symbioses emerges, persists and if or how it impacts mutualistic associations. We developed a metagenomics approach to tease apart strain-level differences in Bathymodiolus symbionts and discovered striking functional differences among co-occurring symbiont strains. This high resolution allows us to study symbiont population structure that helps us understand symbiont colonization dynamics. Using cultivation-independent methods our research provides a snapshot of the symbiosis in its natural context, allowing us to investigate how such strain diversity evolved, persists and how it compares to free-living relatives of the symbionts.

Metabolic investigation of cultivable symbiont relatives

Over the last years, our omic approaches have given us insights into the intricate relationship and metabolic interaction between the Bathymodiolus hosts and their symbionts. To fully show that particular processes take place, we apply manipulative experiments with symbiont relatives such as Methyloprofundus sedimenti, as culturing Bathymodiolus symbionts remains challenging. By using controlled incubation experiments and mass-spectrometry based analyses of the metabolome, we can measure traits of the M. sedimenti genome that are shared with the methane-oxidising symbiont of Bathymodiolus mussels. Not only can we identify possible substrates but also excreted metabolites, which could potentially be available to the host. Our overall aim is to characterize metabolic markers linked to environmental conditions to conclude the recent history of a specimen from the deep-sea with metabolomics data.

Ongoing collaborations with former members of the department

Anne Kupczok, Rebecca Ansorge, Adrien Assié, Antony Chakkiath, Lizbeth Sayavedra, Maxim Rubin-Blum

External collaborators

Deep-sea research in the field

Symbioses in deep-sea snail Ifremeria

One of the most abundant animals at hydrothermal vent systems of the Western Pacific is the snail Ifremeria nautilei. These hosts harbor at least 4 bacterial symbionts in their gills, sulfide- and methane-oxidizing gammaproteobacteria and at least 2 alphaproteobacterial phylotypes of unknown function. We are currently using comparative sequence analysis of phylogenetic and functional genes to gain a better understanding of these symbioses (Borowski et al. in prep.).

Symbiosis in deep-sea shrimp Rimicaris

Rimicaris shrimp form giant swarms on hydrothermal vent chimneys in the Atlantic and Indian oceans. They host a dense community of chemosynthetic epibionts in their modified gill chamber. The epibiosis is dominated by filamentous gamma- and epsilonproteobacteria. Although the epibionts are assumed to contribute to the shrimp's nutrition, direct evidence for this is still lacking. We showed that epibionts on R. exoculata from Mid-Atlantic Ridge vents have distinct biogeographic distribution patterns. We are currently investigating epibiont biogeography on R. hybisae from two vents in the Mid-Cayman Spreading Center, which are only 20 km apart but are separated by 2.5 km water depth. The shrimp epibionts have a free-living stage during their life cycle, and these free-living symbionts are abundant at the vent sites colonized by Rimicaris. We will compare the biogeography of the free-living and host-associated symbionts to answer the question: Is everything everywhere and the partners select?