Page path:

- Press Office

- Press releases 2013

- 18.03.2013 Microbes in the Mariana Trench

18.03.2013 Microbes in the Mariana Trench

Microbes in the Mariana Trench

Highly active communities of bacteria in the world’s deepest oceanic trench.

Sediments of the deepest trench on Earth, Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, shows surprisingly high microbial activity. An international research team led by Professor Ronnie Glud from the University of Southern Denmark involving Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer from the HGF-MPG Joint Research Group on Deep-Sea Ecology and Technology of the Max Planck Institute in Bremen and the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven demonstrated that microbes are numerous and active in this high-pressure environment. Now they published their results in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience.

An international research team presents the first scientific results from one of the most inaccessible places on Earth: the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific, located nearly 11000 meters below sea level, which makes it the deepest site on Earth. Their analyses document that a highly active bacteria community exists in the sediment of the trench - even though the environment is under extreme pressure almost 1,100 times higher than at sea level. The trench sediments are inhabited by almost 7 times more bacteria than in the sediments of the surrounding abyssal plain at a much shallower water depth of 6000 m.

Deep sea trenches are spots of high microbial activity

Deep sea trenches are spots for high microbial activity because they receive an unusually high flux of organic matter, made up of animal carcasses and sinking algae, originating from the surrounding shallower sea-bottom. Some of this material may become dislodged during earthquakes, and sink further down into the deepest regions of the trench. So, even though deep-sea trenches like the Mariana Trench only amount to about two percent of the World Ocean area, they have a relatively large impact on marine carbon balance - and thus on the global carbon cycle, says Professor Ronnie Glud from Nordic Center for Earth Evolution at the University of Southern Denmark. Together with his colleagues from Germany (HGF-MPG Research Group on Deep-Sea Ecology and Technology of the Max Planck Institute in Bremen and Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven), Japan (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) , Scotland (Scottish Association for Marine Science) and Denmark (University of Copenhagen), he explored the microbial carbon turnover in the deepest trench of the oceans.

Highly active communities of bacteria in the world’s deepest oceanic trench.

Sediments of the deepest trench on Earth, Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, shows surprisingly high microbial activity. An international research team led by Professor Ronnie Glud from the University of Southern Denmark involving Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer from the HGF-MPG Joint Research Group on Deep-Sea Ecology and Technology of the Max Planck Institute in Bremen and the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven demonstrated that microbes are numerous and active in this high-pressure environment. Now they published their results in the scientific journal Nature Geoscience.

An international research team presents the first scientific results from one of the most inaccessible places on Earth: the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific, located nearly 11000 meters below sea level, which makes it the deepest site on Earth. Their analyses document that a highly active bacteria community exists in the sediment of the trench - even though the environment is under extreme pressure almost 1,100 times higher than at sea level. The trench sediments are inhabited by almost 7 times more bacteria than in the sediments of the surrounding abyssal plain at a much shallower water depth of 6000 m.

Deep sea trenches are spots of high microbial activity

Deep sea trenches are spots for high microbial activity because they receive an unusually high flux of organic matter, made up of animal carcasses and sinking algae, originating from the surrounding shallower sea-bottom. Some of this material may become dislodged during earthquakes, and sink further down into the deepest regions of the trench. So, even though deep-sea trenches like the Mariana Trench only amount to about two percent of the World Ocean area, they have a relatively large impact on marine carbon balance - and thus on the global carbon cycle, says Professor Ronnie Glud from Nordic Center for Earth Evolution at the University of Southern Denmark. Together with his colleagues from Germany (HGF-MPG Research Group on Deep-Sea Ecology and Technology of the Max Planck Institute in Bremen and Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven), Japan (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) , Scotland (Scottish Association for Marine Science) and Denmark (University of Copenhagen), he explored the microbial carbon turnover in the deepest trench of the oceans.

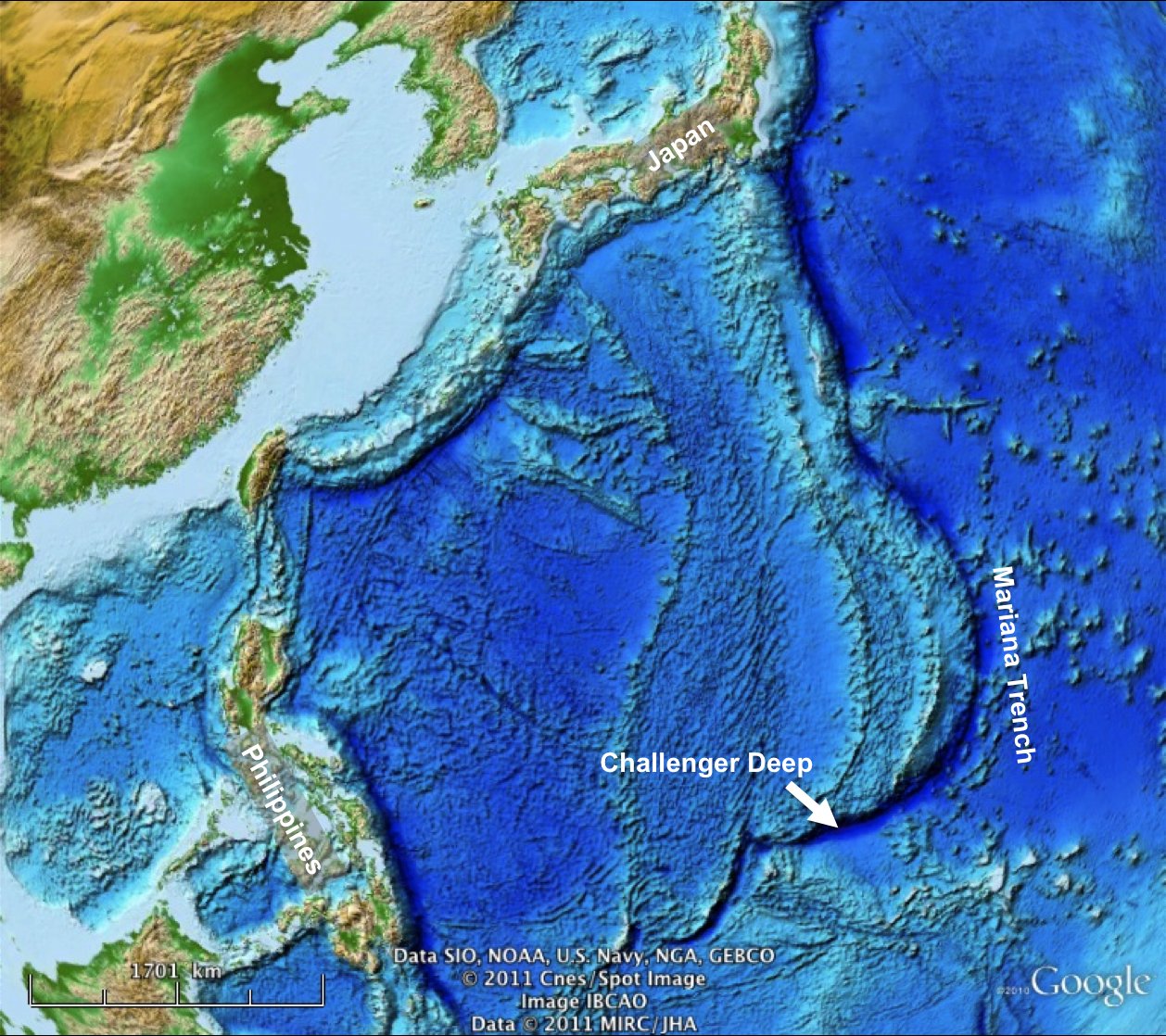

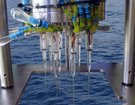

Fig 1: Recovery of the lander after having completed its mission on the seafloor, scientists onboard ship waited three hours for it to return from the bottom of the Trench with its unique data. In total, the sampling was successfully carried out four times (copyright F. Wenzhoefer). Fig 2: Map of the Mariana Trench. The Challenger Depth got its name from the British Research Vessel Challenger II, which mapped the deepest part in 1951. Fig 3: Foto from the seafloor at Challenger Deep (Copyright JAMSTEC)

Fig 4: Life on board RV YOKOSUKA. Ship crew preparing the lander for its deployment (copyright F. Wenzhoefer). 5. The sensors for the oxygen measurements are highly sensitive. (Copyright F. Wenzhöfer).

Technical challenges

The team measured the distribution of oxygen in these trench sediments and at a reference site situated at 6000 m, and took sediment cores with an autonomous coring device that was equipped with a video camera. “From the oxygen profiles we can calculate the microbial oxygen uptake”, says Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer, “Together with the organic carbon content of the seafloor we then can estimate the microbial activity in the sediment.” Of course, those measurements at great depths are technically and logistically challenging “If we retrieve samples from the seabed to investigate them in the laboratory, many of the microorganisms that have adapted to life at these extreme conditions will die, due to the changes in temperature and pressure. Therefore, we have developed instruments that autonomously can perform preprogrammed measuring routines directly on the seabed at the extreme pressure of the Marianas Trench”, says Ronnie Glud. The research team has, together with different companies, designed the underwater robot, which stands almost 4 m tall and weighs 600 kg. Among other things, the robot is equipped with ultrathin sensors that are gently inserted into the seabed to measure the distribution of oxygen at a high spatial resolution.

“Our videos from the bottom of the Mariana Trench confirm that there are very few large animals at these depths. Rather, we find a world dominated by microbes that are adapted to function effectively at conditions highly inhospitable to most higher organisms”, says Ronnie Glud.

Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer not only considers the research on deep sea trenches important for the assessment of their contribution to the global carbon cycle. “The deep sea trenches are some of the last remaining “white spots” on the world map. We are very interested in describing and understanding the unique bacterial communities that thrive in these exceptional environments. Moreover, we aim to understand if and how the microbial carbon turnover in the deep sea regulates our climate. Therefore, we are planning further expeditions to other deep sea trenches, for example to the Kermadec-Tonga Trench near Fiji in the Pacific.”

The team measured the distribution of oxygen in these trench sediments and at a reference site situated at 6000 m, and took sediment cores with an autonomous coring device that was equipped with a video camera. “From the oxygen profiles we can calculate the microbial oxygen uptake”, says Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer, “Together with the organic carbon content of the seafloor we then can estimate the microbial activity in the sediment.” Of course, those measurements at great depths are technically and logistically challenging “If we retrieve samples from the seabed to investigate them in the laboratory, many of the microorganisms that have adapted to life at these extreme conditions will die, due to the changes in temperature and pressure. Therefore, we have developed instruments that autonomously can perform preprogrammed measuring routines directly on the seabed at the extreme pressure of the Marianas Trench”, says Ronnie Glud. The research team has, together with different companies, designed the underwater robot, which stands almost 4 m tall and weighs 600 kg. Among other things, the robot is equipped with ultrathin sensors that are gently inserted into the seabed to measure the distribution of oxygen at a high spatial resolution.

“Our videos from the bottom of the Mariana Trench confirm that there are very few large animals at these depths. Rather, we find a world dominated by microbes that are adapted to function effectively at conditions highly inhospitable to most higher organisms”, says Ronnie Glud.

Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer not only considers the research on deep sea trenches important for the assessment of their contribution to the global carbon cycle. “The deep sea trenches are some of the last remaining “white spots” on the world map. We are very interested in describing and understanding the unique bacterial communities that thrive in these exceptional environments. Moreover, we aim to understand if and how the microbial carbon turnover in the deep sea regulates our climate. Therefore, we are planning further expeditions to other deep sea trenches, for example to the Kermadec-Tonga Trench near Fiji in the Pacific.”

Rückfragen an

Professor Ronnie Glud, Nordic Center for Earth Evolution at the University of Southern Denmark. Phone: +45 65 50 27 84, mobile: +45 60 11 19 13, email: [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer, HGF-MPG Brückengruppe für Tiefsee-Ökologie und –Technologie

[Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Telefon: +49 (0) 421 2028 862

Oder an die Pressesprecher

Dr. Rita Dunker [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript] +49 (0) 421 2028 856

Dr. Manfred Schlösser [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript] +49 (0) 421 2028 704

Originalarbeit

High rate of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth, 2013. Ronnie N. Glud, FrankWenzhöfer, Mathias Middelboe, Kazumasa Oguri,

Robert Turnewitsch, Donald E. Canfield and Hiroshi Kitazato. Nature Geoscience

DOI: 10.1038/NGEO1773

Beteiligte Institute

University of Southern Denmark, Nordic Centre for Earth Evolution, Odense, Dänemark

Scottish Association for Marine Science, Scottish Marine Institute, Oban, Großbrittanien

Greenland Climate Research Centre, Nuuk, Grönland

Max-Planck-Institut für Marine Mikrobiologie, Bremen

Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven

Universität Kopenhagen, Marine Biological Section, Helsingør, Dänemark

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Institute of Biogeosciences, Yokosuka, Japan

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Marine Technology and Engineering Center, Yokosuka, Japan

Professor Ronnie Glud, Nordic Center for Earth Evolution at the University of Southern Denmark. Phone: +45 65 50 27 84, mobile: +45 60 11 19 13, email: [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Dr. Frank Wenzhöfer, HGF-MPG Brückengruppe für Tiefsee-Ökologie und –Technologie

[Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript]

Telefon: +49 (0) 421 2028 862

Oder an die Pressesprecher

Dr. Rita Dunker [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript] +49 (0) 421 2028 856

Dr. Manfred Schlösser [Bitte aktivieren Sie Javascript] +49 (0) 421 2028 704

Originalarbeit

High rate of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth, 2013. Ronnie N. Glud, FrankWenzhöfer, Mathias Middelboe, Kazumasa Oguri,

Robert Turnewitsch, Donald E. Canfield and Hiroshi Kitazato. Nature Geoscience

DOI: 10.1038/NGEO1773

Beteiligte Institute

University of Southern Denmark, Nordic Centre for Earth Evolution, Odense, Dänemark

Scottish Association for Marine Science, Scottish Marine Institute, Oban, Großbrittanien

Greenland Climate Research Centre, Nuuk, Grönland

Max-Planck-Institut für Marine Mikrobiologie, Bremen

Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven

Universität Kopenhagen, Marine Biological Section, Helsingør, Dänemark

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Institute of Biogeosciences, Yokosuka, Japan

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Marine Technology and Engineering Center, Yokosuka, Japan