- Press Office

- Press releases 2021

- Nitrogen inputs in the ancient ocean - underappreciated bacteria step into the spotlight

Nitrogen inputs in the ancient ocean - underappreciated bacteria step into the spotlight

Nitrogen is vital for all forms of life: It is part of proteins, nucleic acids and other cell structures. Thus, it was of great importance for the development of life on early Earth to be able to convert gaseous dinitrogen from the atmosphere into a bio-available form – ammonium. However, it has not yet been clarified who carried out this so-called nitrogen fixation on early Earth and with the help of which enzyme. Now, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen have shown that under similarly barren conditions as in the Proterozoic ocean, a previously underappreciated group of bacteria can fix nitrogen very efficiently.

A “small Proterozoic ocean” in the Swiss Alps

Since the Proterozoic ocean can hardly be studied directly, the researchers Miriam Philippi and Katharina Kitzinger from the Max Planck Institute in Bremen and colleagues substituted it with a comparable modern-day habitat: The alpine Lake Cadagno in Switzerland. Unlike most other lakes, Lake Cadagno is permanently stratified, meaning that the upper and lower water layers do not mix. Purple sulfur bacteria inhabit the transition zone between the upper, oxygenated layer and the lower, oxygen-free and sulfidic layer. There, they carry out photosynthesis and oxidize sulfur. “The discovery of fossils of this group of microorganisms shows that they already lived on our planet at least 1.6 billion years ago, during the Proterozoic eon,” said Philippi, first author of the study. “Hence, this lake and these bacteria represent a system that resembles the Proterozoic ocean in many aspects.” Therefore, it is so well-suited for learning more about the processes on early Earth.

Purple sulfur bacteria fix nitrogen

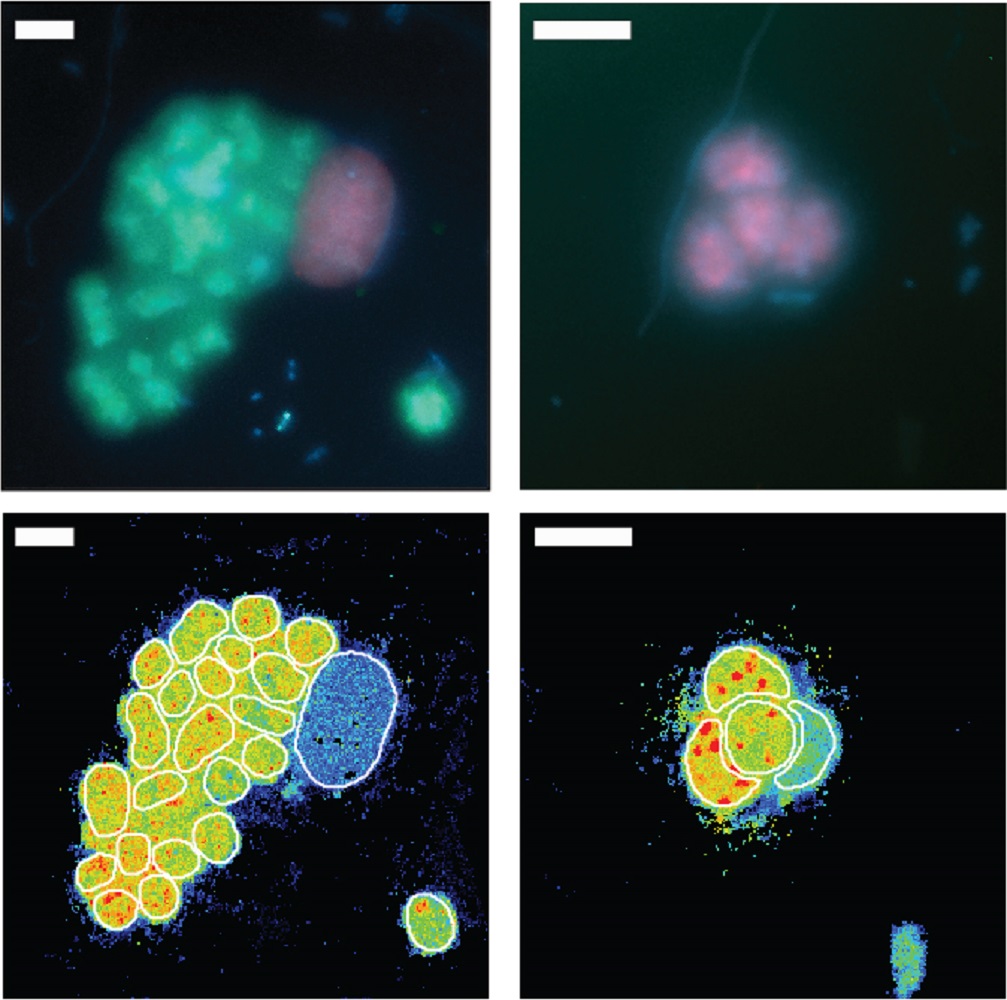

Using a combination of biogeochemical and molecular analyses, Philippi and colleagues discovered that the purple sulfur bacteria in Lake Cadagno fix nitrogen very efficiently. Nitrogen fixation is the conversion of nitrogen gas, which is not very reactive, into nitrogen compounds that many organisms can use, for example algae. “To our knowledge, this is the first direct evidence of nitrogen fixation by purple sulfur bacteria in nature,” explained co-author Katharina Kitzinger. “We discovered that they use the most common enzyme in present-day, molybdenum nitrogenase, to do so. Although this enzyme is not rare, we were very surprised to find it in Lake Cadagno.” This is because there is only very little molybdenum in the water – just as in the Proterozoic ocean, which has led researchers to believe that non-molybdenum nitrogenases prevailed on early Earth. “Now we know that molybdenum nitrogenase works very efficiently, even at low molybdenum concentrations.”

“We thus provide the first indication that purple sulfur bacteria may have been partly responsible for nitrogen fixation in the Proterozoic ocean,” Philippi continued. “Until now, it was generally assumed that cyanobacteria carried out most of the nitrogen fixation then. We show that the role of purple sulfur bacteria in this process was likely underestimated.”

Original publication

Participating institutions

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Department of Environmental Systems Science, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Applied Microbiology Laboratory, University of Applied Sciences of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI), Bellinzona, Switzerland

Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Dübendorf and Kastanienbaum, Switzerland

Please direct your queries to:

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |