- Press Office

- The usual suspects: A close-knit bac...

The usual suspects: A close-knit bacterial community cleans up blooming algae in the North Sea

More than 5 million bacterial genes give a glimpse into microbial processes in the German Bight

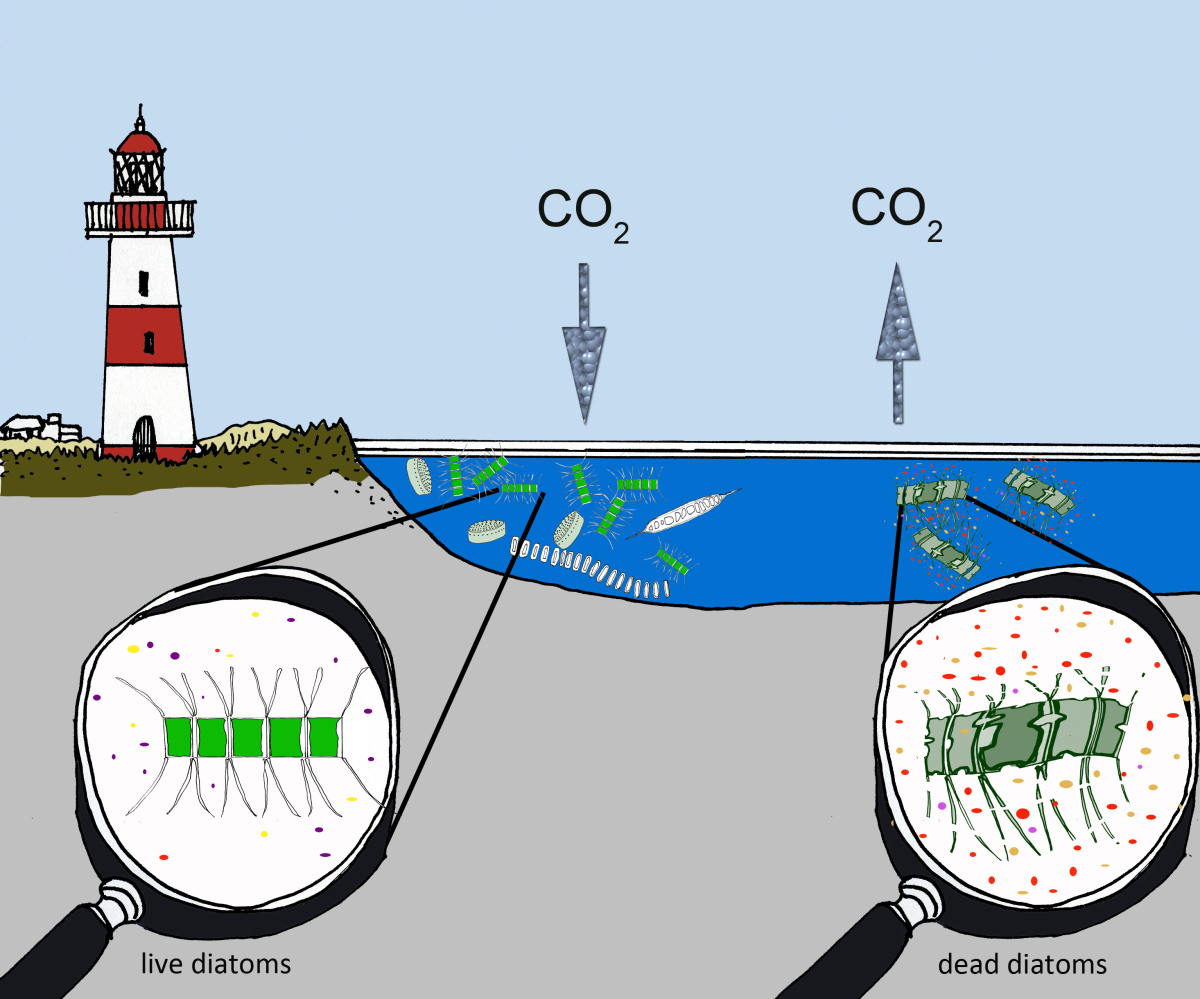

To understand this aspect of the marine carbon cycle we thus need to investigate how the bacterial community in the ocean decomposes the algae. Therefore, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in collaboration with the Biologische Anstalt Helgoland of the Alfred Wegener Institute conducted an extensive study of bacterial and algal dynamics off the island of Helgoland during the annual spring bloom. The researchers led by Hanno Teeling, Bernhard Fuchs and Rudolf Amann from the Bremen Max Planck Institute analysed more than 11,000 data points over a period of four years. They analysed nearly 450 billion base pairs of the meta-genome of the resident bacterial communities. Thereby, they gained information on more than 5 million bacterial genes – corresponding to roughly 200 times the genes of the human genome. There are so many data that the online open access publication, instead of conventional pictures, contains entire posters.

Specialised bacteria break down algal biomass

"From a previous study we know that the bacterial community changes as it degrades the algae spring bloom," says Hanno Teeling. Specialised bacterial groups accompany different stages of the bloom and gradually degrade most of the algal biomass. “The present study reveals: It’s obviously far less important than we thought which algae just have their heyday. In different years, different types of algae can dominate the spring bloom ", explains Bernhard Fuchs. "Regardless, we have always observed a similar sequence of dominant groups of bacteria."

And it’s not only the bacterial groups always showing the same patterns. „Taking a detailed look at the bacterial genes and what they are actually responsible for, it became clear: It is always a similar temporal sequence of genes that regulate the degradation of certain polysaccharides," states Hanno Teeling. "This suggests that different algae in the spring bloom have similar or even the same polysaccharides."

New parts in the carbon puzzle

Next, the researchers from Bremen want to take a close look at the bacterial enzymes that degrade the algal polysaccharides. Which enzymes attack which polysaccharides? What are their exact structures? "From this we can deduce which the main algal polysaccharides are," explains Rudolf Amann. "And with this information we can then add another piece to the puzzle in our understanding of the carbon cycle of the ocean."

Original publication:

Participating institutes

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Helgoland and List auf Sylt, Germany

Please direct your queries to:

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |