Page path:

- Press Office

- Highlights 2000 - 2011

- 10.12.2008 Tiny knights in shining armor – ba...

10.12.2008 Tiny knights in shining armor – bacteria detoxify deadly seawater

Tiny knights in shining armor – bacteria detoxify deadly seawater

Hydrogen sulphide is well known for its characteristic smell of rotten eggs. But hydrogen sulphide is not only smelly, it is also highly toxic. Humans can die within minutes when exposed to high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide. This foul-smelling gas threatens coastal fisheries, which account for 90 percent of global fish-catch. Eutrophication of coastal waters results in the episodic development of sulphidic water masses, with disastrous consequences for coastal ecosystems.

Bacteria play a dubious role in the process – after all, they are responsible for the formation of deadly hydrogen sulphide gas. However, bacteria are also responsible for detoxifying hydrogen sulphide, as researchers from the German Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, the Namibian National Marine Information & Research Centre, the German Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde and the Department of Microbial Ecology of the University of Vienna now discovered. Their surprising results show that bacteria detoxified sulphidic coastal waters covering an area of approximately 7,000 square kilometres off Namibia – an area almost thrice the size of Luxembourg.

Bacteria play a dubious role in the process – after all, they are responsible for the formation of deadly hydrogen sulphide gas. However, bacteria are also responsible for detoxifying hydrogen sulphide, as researchers from the German Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, the Namibian National Marine Information & Research Centre, the German Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde and the Department of Microbial Ecology of the University of Vienna now discovered. Their surprising results show that bacteria detoxified sulphidic coastal waters covering an area of approximately 7,000 square kilometres off Namibia – an area almost thrice the size of Luxembourg.

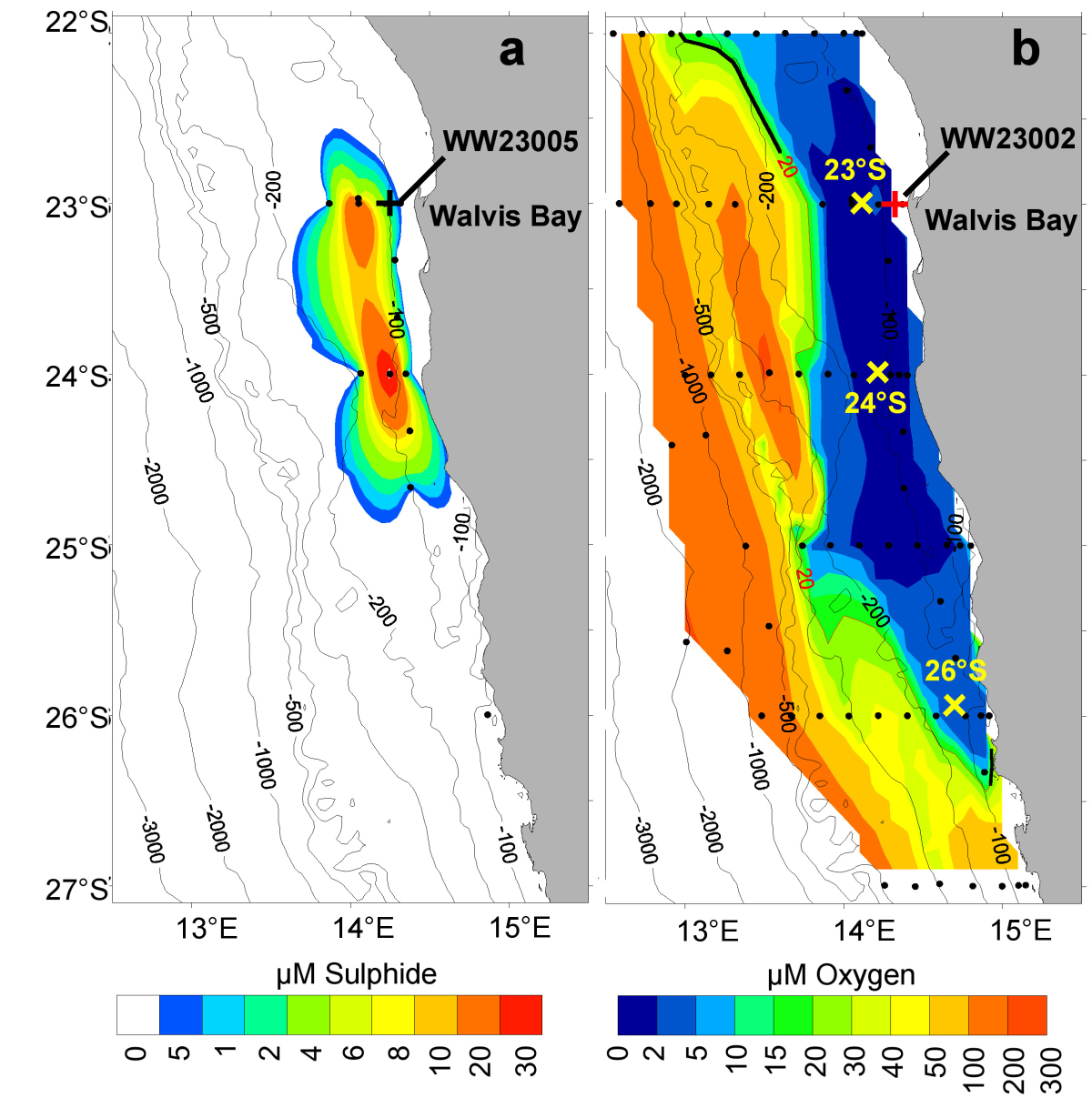

Figure 2: Concentration of sulphide and oxygen off the Namibian coast in January 2004. The left panel shows the amount of sulphide two meters above the sea floor. Red colour means very high, blue comparatively low concentrations. The right panel shows simultaneously measured oxygen concentrations. The dark blue area is completely depleted in oxygen. At the sea surface, this layer was not visible and therefore not registered by satellites. (taken from the publication)

The scientists investigated the occurrence of sulphidic water masses along the coast of West Africa. In January 2004, they hit upon a sulphidic water mass covering 7,000 square kilometres of coastal seafloor. The surface waters, however, were well oxygenated. In the presence of oxygen, sulphide is oxidized and transformed into nontoxic forms of sulphur. Surprisingly, Lavik, Stührmann, Kuypers and their colleagues found an intermediate layer in the water column, which contained neither hydrogen sulphide nor oxygen. What had happened to the poisonous gas?

“Obviously it was oxidized anaerobically – without oxygen”, Torben Stührmann explains. “Many bacteria do not require oxygen for respiration and can use nitrate instead. And indeed – we found a water layer that contained both hydrogen sulphide and nitrate.”

“Obviously it was oxidized anaerobically – without oxygen”, Torben Stührmann explains. “Many bacteria do not require oxygen for respiration and can use nitrate instead. And indeed – we found a water layer that contained both hydrogen sulphide and nitrate.”

This water layer is the habitat of detoxifying microorganisms, which are closely related to bacteria known from hot vents and cold seeps in the deep ocean. By using nitrate, these bacteria transform sulphide into finely dispersed particles of sulphur that are nontoxic. Thus, the microorganisms create a buffer zone between the toxic deep water and the oxygenated surface waters, where fish and other marine animals live.

These results, published in the journal “Nature”, are not only relevant for West African fisheries. They also suggest that animals living on or near the seafloor in coastal waters all over globe may be affected by such toxic water masses more often than previously thought. Up to now, sulphidic water masses were monitored with the help of satellites, taking pictures of the sea surface while orbiting the earth. Sulphur shows up in satellite pictures as whitish/turquoise discolorations of surface water. However, many of these sulphidic events may go unnoticed by satellite because bacteria consume the hydrogen sulphide before it reaches the surface. “We assume that there are many more of these sulphidic events than previously thought”, Namibian marine scientist Anja van der Plas comments. “Yet, they go unnoticed using conventional methods.”

These results, published in the journal “Nature”, are not only relevant for West African fisheries. They also suggest that animals living on or near the seafloor in coastal waters all over globe may be affected by such toxic water masses more often than previously thought. Up to now, sulphidic water masses were monitored with the help of satellites, taking pictures of the sea surface while orbiting the earth. Sulphur shows up in satellite pictures as whitish/turquoise discolorations of surface water. However, many of these sulphidic events may go unnoticed by satellite because bacteria consume the hydrogen sulphide before it reaches the surface. “We assume that there are many more of these sulphidic events than previously thought”, Namibian marine scientist Anja van der Plas comments. “Yet, they go unnoticed using conventional methods.”

Figure 5: Pilot whales swim around the research vessel R/V A.v.Humboldt (Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology, Gaute Lavik). The sulphidic water mass forces fishes, squids and shrimps to the sea surface, where they are eaten by whales, dolphins, seals and seabirds. “During our previous scientific cruises to these waters we have never seen so many marine animals in one place as during the sulphidic event in January 2004” cruise leader Ulrich Lass recounts.

“There is a very positive as well as a worrying aspect of our discovery of a gigantic bacterial bloom detoxifying hydrogen sulphide”, summarizes group leader Marcel Kuypers, “Hydrogen sulphide is toxic to higher life and even at low concentrations it will instantly kill fish, oysters, shrimps and lobsters. The good news is that the discovered groups of bacteria seem to consume the hydrogen sulphide before it reaches the surface waters where fish are living. It is worrying news, however, that an area the size of the Irish Sea or the Wadden Sea was affected by sulphidic bottom waters, without this being visible on satellite photos or detected at the monitoring stations closer to the coast.”

Mass death by suffocation in coastal waters is not restricted to the coast off southwest Africa, where sulphidic events occur naturally. It has also been reported for coastal waters off India, California, the Gulf of Mexico as well as European coastal waters. “There is increasing evidence demonstrating that global warming and high anthropogenic nutrient load to coastal waters are causing more frequent coastal anoxia, which in turn increases the risk of sulphide in coastal waters”, Gaute Lavik explains. “However, the fact that we can correlate sulphidic waters with certain environmental conditions might provide an opportunity to forecast these events in the future.”

Background: Toxic hydrogen sulphide

Hydrogen sulphide develops in anoxic environments where sulphate respiring bacteria -so-called sulphate reducers- degrade animal or plant remains. The conspicuous smell of rotten eggs is a striking warning that this toxic gas is released. At first, the gas irritates human eyes and respiratory tracts and higher concentrations result in death by apnoea within seconds.

Some scientists think that hydrogen sulphide is responsible for mass extinctions of numerous animal and plant species in the early history of the Earth. They argue that declining oxygen concentrations in the oceans could have caused hydrogen sulphide to rise from deeper water layers. Subsequently, the toxic gas was released into the atmosphere, unfolding its deadly impact on the land ecosystem.

Some scientists think that hydrogen sulphide is responsible for mass extinctions of numerous animal and plant species in the early history of the Earth. They argue that declining oxygen concentrations in the oceans could have caused hydrogen sulphide to rise from deeper water layers. Subsequently, the toxic gas was released into the atmosphere, unfolding its deadly impact on the land ecosystem.

Fanni Aspetsberger

For further information please contact:

Dr. Marcel Kuypers 0421 2028 647

Dr. Gaute Lavik 0421 2028 651

Torben Stührmann 0421 2208 322

or the MPI press officers

Dr. Manfred Schlösser 0421 2028 704

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger 0421 2028 704

Dr. Marcel Kuypers 0421 2028 647

Dr. Gaute Lavik 0421 2028 651

Torben Stührmann 0421 2208 322

or the MPI press officers

Dr. Manfred Schlösser 0421 2028 704

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger 0421 2028 704

Original article:

Detoxification of sulphidic African shelf waters by blooming chemolithotrophs. Gaute Lavik, Torben Stührmann, Volker Brüchert, Anja Van der Plas, Volker Mohrholz, Phyllis Lam, Marc Mußmann, Bernhard M. Fuchs, Rudolf Amann, Ulrich Lass & Marcel M. M. Kuypers.

DOI 10.1038/nature07588

Participating institutions:

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Celsiusstrasse 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

National Marine Information & Research Centre Ministry of Fisheries & Marine Resources, PO Box 912, Swakopmund, Namibia.

Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde, Seestrasse 15, D-18119 Rostock, Germany.

Department of Microbial Ecology, Vienna Ecology Centre, University of Vienna, Althanstraße 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

Detoxification of sulphidic African shelf waters by blooming chemolithotrophs. Gaute Lavik, Torben Stührmann, Volker Brüchert, Anja Van der Plas, Volker Mohrholz, Phyllis Lam, Marc Mußmann, Bernhard M. Fuchs, Rudolf Amann, Ulrich Lass & Marcel M. M. Kuypers.

DOI 10.1038/nature07588

Participating institutions:

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Celsiusstrasse 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

National Marine Information & Research Centre Ministry of Fisheries & Marine Resources, PO Box 912, Swakopmund, Namibia.

Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde, Seestrasse 15, D-18119 Rostock, Germany.

Department of Microbial Ecology, Vienna Ecology Centre, University of Vienna, Althanstraße 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria

Figure 1: Tip of the iceberg? A large patch of discolored surface waters off Namibia attributed to toxic hydrogen sulphide release from the seafloor. Many of these naturally occurring events may go unnoticed by satellite because bacteria consume sulphide before it reaches the surface. (Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC,

http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_rec.php?id=4976)

http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_rec.php?id=4976)

Figure 3: Siegfried Krüger, engineer and technician at the Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde, handling the pump-CTD. (Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology, Gaute Lavik)

Figure 4: Author Gaute Lavik and technician Gabriele Klockgether on board RV A. v. Humboldt. (Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology, Gaute Lavik)