Page path:

- Press Office

- Press releases 2013

- 21.01.2013 Wood on the seafloor

21.01.2013 Wood on the seafloor

Wood on the seafloor- an oasis for deep-sea life

Trees do not grow in the deep sea, nevertheless sunken pieces of wood can develop into oases for deep-sea life - at least temporarily until the wood is fully degraded. A team of Max Planck researchers from Germany now showed how sunken wood can develop into an attractive habitats for a variety of microorganisms and invertebrates. By using underwater robot technology, they confirmed their hypothesis that animals from hot and cold seeps would be attracted to the wood due to the activity of bacteria, which produce hydrogen sulfide during wood degradation.

Many of the animals thriving at hydrothermal vents and cold seeps require special forms of energy such as methane and hydrogen sulfide emerging from the ocean floor. They carry bacterial symbionts in their body, which convert the energy from these compounds into food. The vents and seeps are often separated by hundreds of kilometers of deep-sea desert, with no connection between them.

For a long time it was an unsolved mystery how animals can disperse between those rare oases of energy in the deep sea. One hypothesis was that sunken whale carcasses, large dead algae, and also sunken woods could serve as food source and temporary habitat for deep-sea animals, but only if bacteria were able to produce methane and sulfur compounds from it.

Trees do not grow in the deep sea, nevertheless sunken pieces of wood can develop into oases for deep-sea life - at least temporarily until the wood is fully degraded. A team of Max Planck researchers from Germany now showed how sunken wood can develop into an attractive habitats for a variety of microorganisms and invertebrates. By using underwater robot technology, they confirmed their hypothesis that animals from hot and cold seeps would be attracted to the wood due to the activity of bacteria, which produce hydrogen sulfide during wood degradation.

Many of the animals thriving at hydrothermal vents and cold seeps require special forms of energy such as methane and hydrogen sulfide emerging from the ocean floor. They carry bacterial symbionts in their body, which convert the energy from these compounds into food. The vents and seeps are often separated by hundreds of kilometers of deep-sea desert, with no connection between them.

For a long time it was an unsolved mystery how animals can disperse between those rare oases of energy in the deep sea. One hypothesis was that sunken whale carcasses, large dead algae, and also sunken woods could serve as food source and temporary habitat for deep-sea animals, but only if bacteria were able to produce methane and sulfur compounds from it.

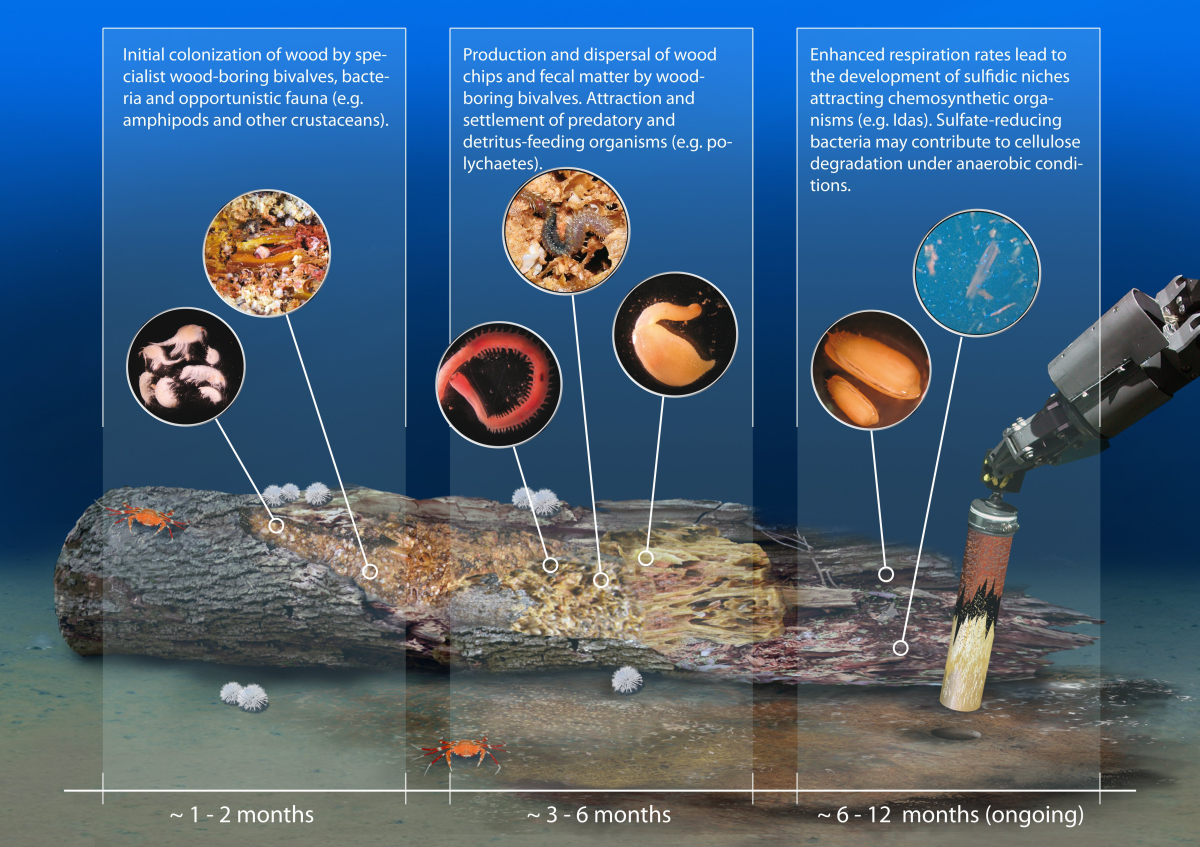

Colonization of wood in the deep sea. (© Bienhold et al., PLoS ONE 8(1): e53590).

To tackle this question, the team deposited wood logs on the Eastern Mediterranean seafloor at depths of 1700 meters and returned after one year to study the fauna, bacteria, and chemical microgradients.

“We were surprised how many animals had populated the wood already after one year. The main colonizers were wood-boring bivalves of the genus Xylophaga, also named “shipworms” after their shallow-water counterparts. The wood-boring Xylophaga essentially constitute the vanguard and prepare the habitat for other followers,” Bienhold said. „But they also need assistance from bacteria, namely to make use of the cellulose from the wood, which is difficult to digest.”

The team of researchers observed that the wood-boring bivalves had cut large parts of the wood into smaller chips, which were further degraded by many other organisms. This activity led to the consumption of oxygen, enabling the production of hydrogen sulfide by sulfate-reducing microorganisms. And indeed, the researchers also found a mussel, which is typically only found at cold seeps or similar environments where it uses sulfur compounds as an energy source. “It is amazing to see how deep-sea bacteria can transform foreign substances such as wood to provide energy for cold-seep mussels on their journey through the deep ocean”, said Antje Boetius, chief scientist of the expedition. Furthermore, the researchers discovered unknown species of deep-sea worms, which have been described by taxonomic experts in Germany and the USA. Thus, sunken woods do not only promote the dispersal of rare deep-sea animals, but also form hotspots of biodiversity at the deep seafloor.

Manfred Schlösser

This study was part of the German-French project DIWOOD, which is supported by the Max Planck society and the CNRS. Further support came from the EU Projects HERMES (6 FP) and HERMIONE (7 FP).

“We were surprised how many animals had populated the wood already after one year. The main colonizers were wood-boring bivalves of the genus Xylophaga, also named “shipworms” after their shallow-water counterparts. The wood-boring Xylophaga essentially constitute the vanguard and prepare the habitat for other followers,” Bienhold said. „But they also need assistance from bacteria, namely to make use of the cellulose from the wood, which is difficult to digest.”

The team of researchers observed that the wood-boring bivalves had cut large parts of the wood into smaller chips, which were further degraded by many other organisms. This activity led to the consumption of oxygen, enabling the production of hydrogen sulfide by sulfate-reducing microorganisms. And indeed, the researchers also found a mussel, which is typically only found at cold seeps or similar environments where it uses sulfur compounds as an energy source. “It is amazing to see how deep-sea bacteria can transform foreign substances such as wood to provide energy for cold-seep mussels on their journey through the deep ocean”, said Antje Boetius, chief scientist of the expedition. Furthermore, the researchers discovered unknown species of deep-sea worms, which have been described by taxonomic experts in Germany and the USA. Thus, sunken woods do not only promote the dispersal of rare deep-sea animals, but also form hotspots of biodiversity at the deep seafloor.

Manfred Schlösser

This study was part of the German-French project DIWOOD, which is supported by the Max Planck society and the CNRS. Further support came from the EU Projects HERMES (6 FP) and HERMIONE (7 FP).

One of the wood experiments after one year at the seafloor. Wood-boring bivalves of the genus Xylophaga had populated the wood.