- Press Office

- Press releases

- Breathing poison: Microbial life on nitric oxide respiration

Breathing poison: Microbial life on nitric oxide respiration

Nitric oxide (NO) is a fascinating and versatile molecule, important for all living things as well as the environment. It is highly reactive and toxic, organisms use it as a signaling molecule, it depletes the ozone layer in our planet’s atmosphere, and it is the precursor of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide (N2O). Moreover, NO might have played a fundamental role in the emergence and evolution of life on Earth, as it was available as a high-energy oxidant long before there was oxygen.

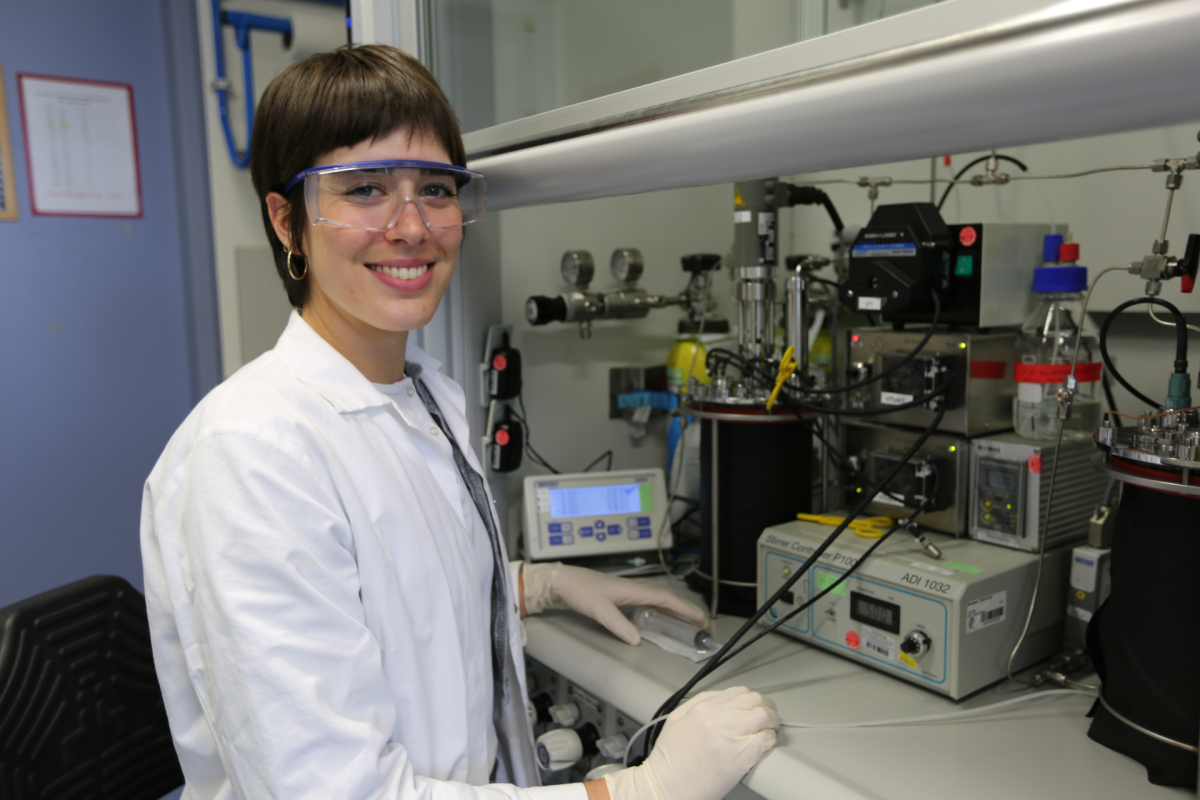

Thus, despite its toxicity, it makes perfect sense that microbes use NO to grow. However, research on the topic is scarce and, to date, microbes growing on it have not been cultivated. That has now changed, as reported by scientists around Paloma Garrido Amador and Boran Kartal from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, in the journal Nature Microbiology. They have managed to enrich two yet unknown species of microorganisms growing on NO in bioreactors and reveal exciting aspects of their lifestyle.

From the wastewater tank to the bioreactor

The study started off with a trip to Bremen’s wastewater treatment plant. “We collected sludge from their denitrifying tank”, Garrido Amador tells. “Back in our lab, we added the sludge to one of our bioreactors and we started the incubation by feeding it with NO.” Bioreactors are designed and optimized to grow microorganisms under controlled conditions, which closely mimic their natural environment. This bioreactor setup was very challenging, though, Garrido Amador reports, “Because NO is toxic, we needed special equipment and had to take great care when handling them for our own safety. Nevertheless, we managed to keep the cultures growing for more than four years now – and they are still happy and healthy!”

Two new microorganisms

The living conditions in the bioreactor thus favored microorganisms that could survive and grow anaerobically with NO. “Eventually, two previously unknown species turned out to dominate the culture”, says Boran Kartal, group leader of the Microbial Physiology Research Group the Max Planck Institute in Bremen. “We named them Nitricoxidivorans perserverans and Nitricoxidireducens bremensis.” Garrido Amador adds, “From just two microorganisms growing on NO, we gained valuable insight into how non-model microorganisms, in particular NO-reducers grow. Some of our observations showed us that these microbes did not conform to how model organisms – organisms which easily cultivated and thus extensively studied – behave, and showcased the limitations of metabolic predictions based solely on genome analyses.”

Importance in the environment and applications for waste removal

“Currently we know little about the contribution of microorganisms growing on NO to nitrogen cycling in natural and engineered environments”, explains Kartal. “Nevertheless, we can speculate that these microorganisms could potentially be feeding on NO and N2O released by other microorganisms while removing nitrosative stress and minimizing the emission of these climate active gases to the atmosphere.”

The enriched microorganisms converted NO to dinitrogen (N2) very efficiently. “There were virtually no emissions of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide”, Kartal adds. The latter – the sole production of N2 – is particularly relevant for application: Many other microorganisms convert NO to nitrous oxide, which is a potent greenhouse gas. N2, in contrast, is harmless. Thus, each molecule of NO that is transformed into N2 instead of nitrous oxide is one less molecule adding to climate change.

In a next step, the Max Planck researchers are cultivating other NO-respiring microorganisms using samples from natural and engineered environments. “Cultivation and enrichment of further NO-respiring microorganisms will help to elucidate the evolution of N-oxide reduction pathways and the enzymes involved. It will also allow to decipher the role of NO in known and yet-unknown processes of the nitrogen cycle and its importance in the natural and engineered environments where these processes take place.”, Garrido Amador concludes.

Original publication

Paloma Garrido-Amador, Niek Stortenbeker, Hans J.C.T. Wessels, Daan R. Speth, Inmaculada Garcia-Heredia, Boran Kartal (2023): Enrichment and characterization of a nitric oxide-reducing microbial community in a continuous bioreactor. Nature Microbiology (2023). Published online July 10, 2023.

DOI: 10.1038/s41564-023-01425-8

Participating institutions

- Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Celsiusstraße 1, 28359, Bremen, Germany

- Translational Metabolic Laboratory, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert Grootepleinzuid 10, 6525GA, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

- School of Science, Constructor University, Campus Ring 1, 28759, Bremen, Germany

Further reading

Please direct your queries to:

Microbial Physiology Research Group

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3137 |

|

Phone: |

Group leader

Microbial Physiology Research Group

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3126 |

|

Phone: |

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |